Long before the Roman legions marched across the Iberian Peninsula, carving out the province of Hispania, the mist-shrouded green hills of the northwest were home to a people forged by the land itself. They were the Gallaeci, a mosaic of Celtic tribes renowned for their martial prowess, unique culture, and the extraordinary fortified settlements from which they ruled their world. These were not the scattered barbarians of Roman propaganda but a complex Iron Age society whose legacy of fierce independence is etched into the very landscape of modern-day Galicia, northern Portugal, and Asturias.

A Land of Hills and Forts: The Castro Culture

To understand the Gallaeci, one must first understand their home: the castro. Dotted across the highlands and coastal promontories, these fortified hillforts were the heart of Gallaecian life. More than just military outposts, they were bustling, self-sufficient towns, the epicenters of social, economic, and religious activity. A typical castro was strategically perched on a hill, offering commanding views of the surrounding valleys and rivers.

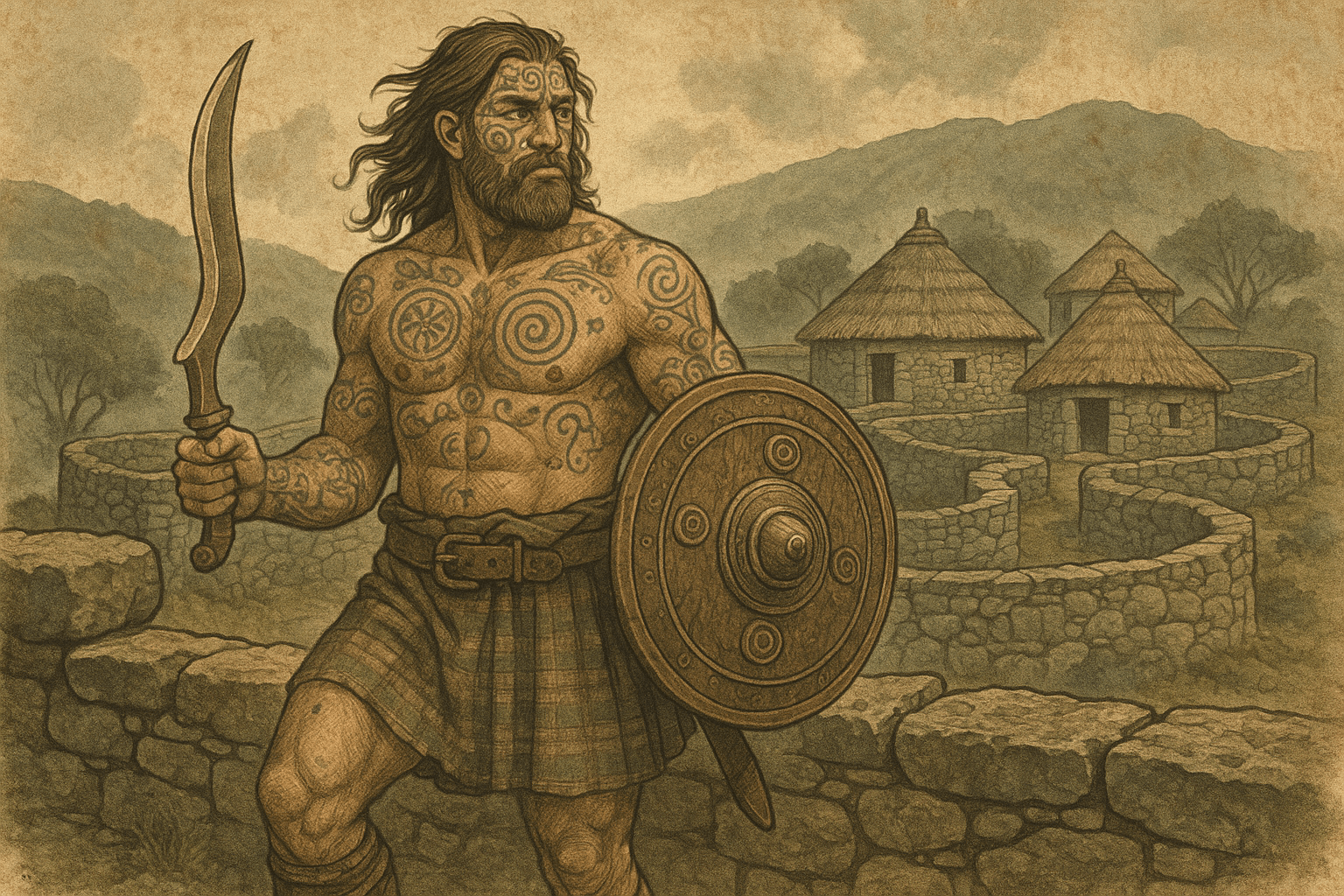

Their construction was a marvel of defensive engineering. Most were protected by one or more concentric rings of massive stone walls, interspersed with deep ditches and formidable ramparts. Within these defenses, the community lived in distinctive circular or oblong stone houses with thatched conical roofs. Clustered together along narrow, winding pathways, these dwellings created a communal and highly defensible living space. Today, the ruins of over 5,000 castros, like the spectacular coastal Castro de Santa Trega, stand as silent testament to this remarkable architectural and social tradition, which flourished from the 9th century BC until after the Roman conquest.

Gallaecian Society: Clans, Chieftains, and Cauldrons

Gallaecian society was tribal, organized around kinship groups and clans (gentilitates) who owed allegiance to a chieftain or a warrior aristocracy. This elite class demonstrated its power not only through military leadership but also through wealth, especially in the form of intricate goldwork. The region was rich in gold, and Gallaecian artisans were master goldsmiths, crafting stunning torcs (neck rings), bracelets, and earrings that served as powerful symbols of status and authority.

Life revolved around a mixed economy of agriculture, herding cattle, and extensive trade. Within the castro walls, the community was paramount. Feasting played a crucial role in binding the society together, reinforcing social hierarchies and celebrating military victories. The bronze cauldron, often a centerpiece of these feasts, became a potent symbol of hospitality, wealth, and the chieftain’s ability to provide for his people.

The Gallaecian Warrior: Forged in Metal and Myth

The Gallaecians were, above all, warriors. Roman historians like Strabo and Appian described them with a mixture of fear and respect, noting their unyielding spirit and preference for guerrilla warfare. They were perfectly adapted to their rugged, forested terrain, using ambushes and lightning-fast raids to confound their enemies. For the Gallaecian man, the path of the warrior was a defining aspect of his identity.

Archaeology and stone sculptures—most famously the monumental “Guerreiros Galaicos” or Gallaecian Warrior statues found in northern Portugal—give us a vivid picture of their martial appearance:

- The Caetra: Their most iconic piece of equipment was the caetra, a small, round wooden shield with a central metal boss. It was light and maneuverable, ideal for their fast-paced style of combat.

- Swords and Daggers: They wielded short swords, often of the “antenna-hilted” type common among Celtic peoples, and daggers for close-quarters fighting.

- Spears and Javelins: The primary offensive weapons were spears for thrusting and a volley of javelins to be hurled at the start of an engagement.

- The Torc: Elite warriors wore heavy, ornate gold torcs not only as a sign of rank but also as a form of spiritual protection.

Perhaps most shocking to the patriarchal Romans was the role of Gallaecian women. Classical sources report that women often fought alongside the men, defending their homes with the same ferocity. They were not seen as passive bystanders but as integral members of the community’s defense, a tradition that underscored the Gallaeci’s all-encompassing commitment to protecting their kin and land.

Collision with an Empire: Resisting Rome

The Gallaeci’s first significant clash with Rome came in 137 BC, when the consul Decimus Junius Brutus led a punitive expedition into their territory. He fought his way to the Minho River and beyond, earning the honorary title Callaicus for his campaign. Yet, his was a temporary victory. For the next century, the Gallaeci remained largely independent, a constant, nagging problem on the empire’s northwestern frontier.

The final subjugation came under the reign of Emperor Augustus. The Cantabrian Wars (29-19 BC) were a brutal, decade-long struggle to pacify the last independent peoples of Iberia. Rome threw its finest legions, led by the brilliant general Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, against the Gallaeci and their Cantabrian allies. The Romans were frustrated by the difficult terrain and the hit-and-run tactics of the native warriors. According to the historian Cassius Dio, the Gallaeci would rather take their own lives than face enslavement. The war was one of attrition and extermination, with Rome eventually prevailing through overwhelming force and by systematically destroying the castros. The primary motivation for this immense military effort was not just strategic control, but the lure of the region’s vast gold deposits, which Augustus needed to finance his empire.

The Enduring Legacy

Though conquered and eventually integrated into the Roman Empire, the spirit of the Gallaeci was never truly extinguished. Their culture fused with Roman influences, creating a unique Gallaeco-Roman society. Their language faded, replaced by a form of provincial Latin that would eventually evolve into modern Galician and Portuguese.

But their legacy endures. It lives on in the thousands of castro ruins that crown the hills, in the Celtic motifs found in local art, and in the fierce, independent character still associated with the people of this region. The Gallaecian warriors were far more than a footnote in Rome’s story of conquest; they were a proud and resilient people who defended their world to the last and left an indelible mark on the soul of Iberia.