From Weavers to Merchant Princes

The Fugger story begins humbly. In 1367, a weaver named Hans Fugger moved from a rural village to the bustling free imperial city of Augsburg. He was a skilled craftsman, and the family business in textiles grew steadily. However, it was Hans’s grandsons, Ulrich, Georg, and especially Jakob Fugger, who transformed the family’s modest wealth into a global enterprise.

Nicknamed “Jakob the Rich”, he was the visionary architect of the family’s financial empire. Sent to Venice as a young man, he immersed himself in the cutting-edge world of Italian banking, mastering the art of double-entry bookkeeping and cultivating connections. He realized that the real money wasn’t just in trading finished goods, but in controlling the raw materials. With audacious foresight, Jakob began investing heavily in mining, securing monopolies on silver from Tyrol and copper from Hungary. This control over Europe’s essential metals became the bedrock of the Fugger fortune.

Jakob the Rich: The Architect of an Empire

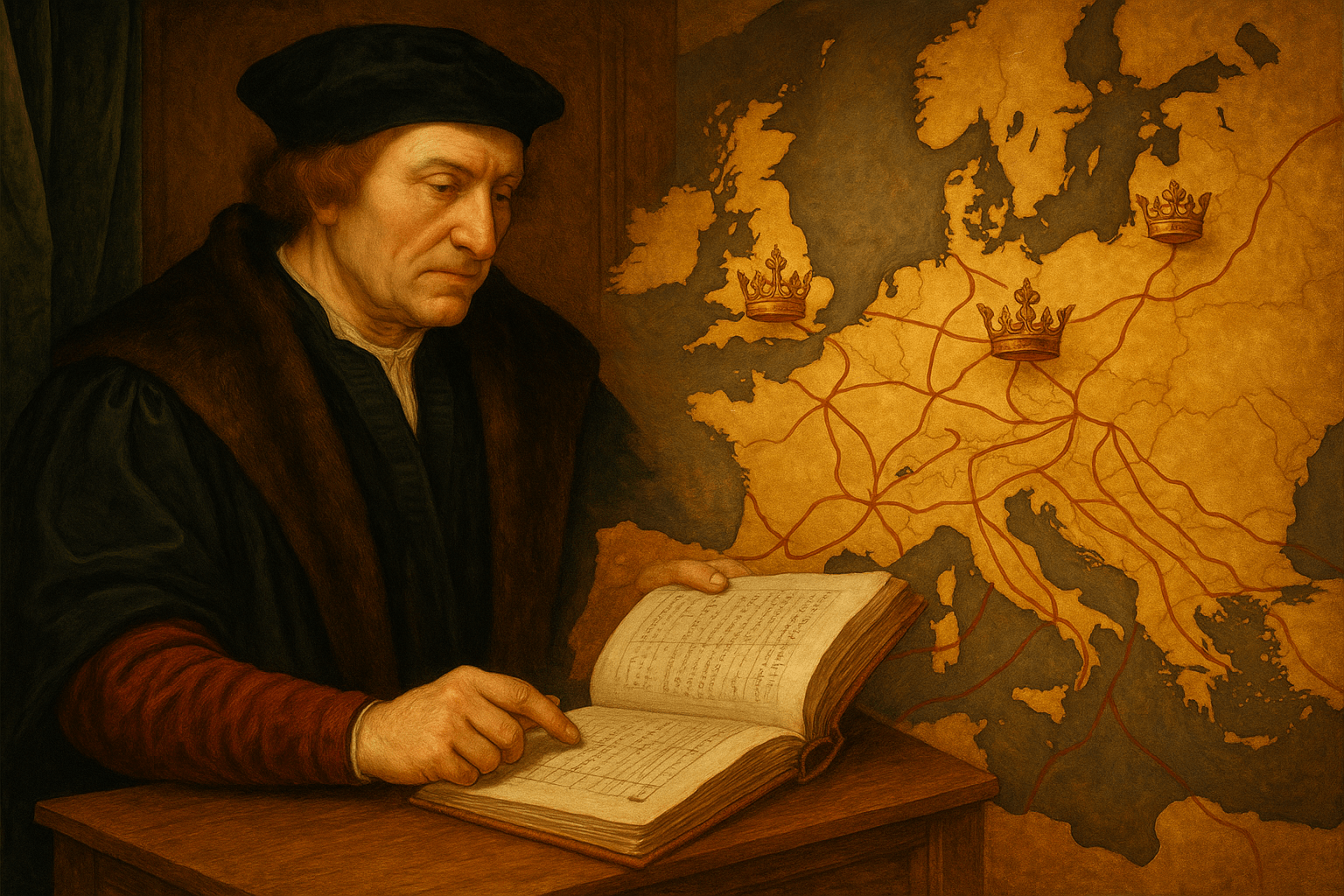

Jakob Fugger was more than just a merchant; he was a pioneer of early capitalism. His business was a complex, multinational corporation with interests spanning from mining and spices to international banking. He understood that information was as valuable as gold. To that end, the Fuggers established a private intelligence network, the Fugger-Zeitungen (Fugger Newsletters). This system of handwritten reports, sent by correspondents from across the known world, gave Jakob an unparalleled advantage, allowing him to anticipate market shifts, political turmoil, and opportunities for investment long before his rivals.

He was a ruthless businessman who pursued debts with vigor, but he also took calculated risks that others would not dare. He financed monarchs when their treasuries were empty and bailed out nobles on the brink of ruin, always ensuring the terms were heavily in his favor. His motto was reputedly, “I want to gain while I can.” And gain he did.

Banking for the House of Habsburg

The Fuggers’ most significant clients were the Habsburgs, the dynasty that dominated Central European politics. The relationship began with Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I, a ruler with grand ambitions but chronically empty coffers. The Fuggers bankrolled his military campaigns and lavish court, and in return, they received lucrative mining rights, tax concessions, and titles of nobility.

The family’s political influence reached its zenith in 1519 with the election of the Holy Roman Emperor. The two main candidates were King Francis I of France and Charles I of Spain (the future Emperor Charles V). The title wasn’t hereditary; it was decided by the votes of seven prince-electors who expected to be handsomely compensated. As Francis I began distributing French gold, Charles turned to the only people who could out-spend a king: the Fuggers.

Jakob Fugger orchestrated a staggering campaign of bribery on Charles’s behalf. Of the 850,000 gold florins needed to secure the election, the Fuggers lent an incredible 543,000. It was a loan that changed the course of European history. With Fugger money lining their pockets, the electors chose Charles, who became the immensely powerful Emperor Charles V. In a stunning display of his power, Jakob later sent the new emperor a letter pointedly reminding him, “It is well known and clear as day that Your Imperial Majesty would not have gained the Roman Crown without my help.”

Financing Popes and Fueling the Reformation

The Fuggers’ influence extended beyond secular rulers to the highest office of the Catholic Church. They managed papal finances and transferred funds across Europe. Their most fateful involvement, however, was in the business of indulgences—the practice of paying the Church to reduce time in purgatory.

In 1515, Archbishop Albrecht of Mainz needed a massive sum of money to pay the pope for permission to hold multiple bishoprics, a violation of church law. Pope Leo X, who needed funds to rebuild St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, agreed. The Fuggers brokered the deal. Here’s how it worked:

- The Fuggers loaned the entire sum to Archbishop Albrecht.

- To repay the loan, the Archbishop was granted permission to oversee a special sale of indulgences in his territories.

- Half the proceeds from the indulgence sales went to the Fuggers to repay the debt, and the other half went to the Pope in Rome.

This aggressive and commercialized sale of salvation, managed by Fugger agents alongside church officials, outraged a certain German monk named Martin Luther. In 1517, he nailed his Ninety-five Theses to a church door in Wittenberg, directly challenging the practice. While the causes of the Protestant Reformation were complex, the Fuggers’ financial engineering was the direct, proximate spark that lit the flame.

The Price of Power: Decline of a Dynasty

At its peak under Jakob’s nephew, Anton Fugger, the family’s wealth was estimated to be around 2% of Europe’s entire GDP. But a business model built on lending to monarchs is inherently risky. The Fuggers’ fortunes were inextricably tied to the House of Habsburg. Charles V’s son, Philip II of Spain, inherited a vast empire but also colossal debts. He declared state bankruptcy multiple times, effectively wiping out huge portions of the Fugger loans.

Simultaneously, the economic center of Europe was shifting from Central Europe to the Atlantic coast. The influx of silver from the New World devalued the Fuggers’ European mines, and new centers of commerce like Antwerp, Amsterdam, and London rose to prominence. Faced with mounting losses and a changing world, the Fuggers gradually withdrew from high-risk international banking. They transitioned from being Europe’s financiers to becoming wealthy, landed aristocrats, managing their vast estates. Their era of world-shaking influence was over.

An Enduring Legacy

Though their banking empire faded, the Fuggers left an indelible mark on history. They demonstrated how private wealth could steer the course of international politics, creating a model for “too big to fail” finance that resonates to this day. But their legacy is not purely one of power and profit. In 1521, Jakob Fugger founded the Fuggerei in Augsburg—the world’s oldest social housing complex still in use. For an annual rent of just one Rhenish guilder (equivalent to €0.88 today), needy Catholic citizens of Augsburg can find a home. It stands as a testament to the family’s complex legacy, a blend of ruthless ambition and remarkable philanthropy that defined one of history’s most powerful families.