When we hear the name “First Opium War”, the story seems simple: a moralistic China tried to ban a destructive drug, and a cynical Britain went to war to force it upon them. It’s a narrative of pure imperial villainy versus well-intentioned victimhood. While there’s undeniable truth to Britain’s shameful role in trafficking the drug, this simple story obscures the deeper, more complex engine driving the conflict. Opium wasn’t the cause of the war; it was the symptom and, for Britain, the diabolical solution to a much bigger problem.

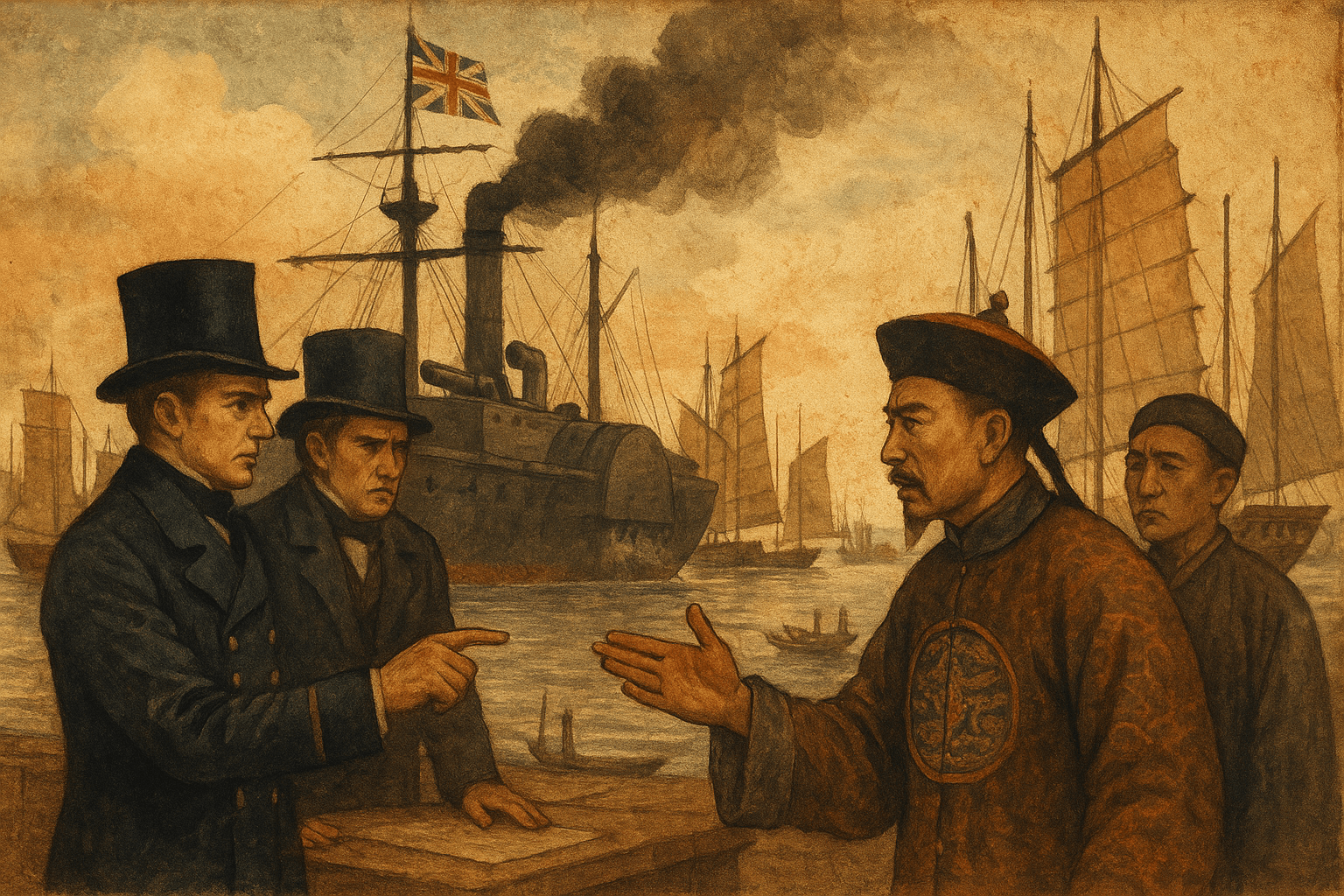

The true story is a collision of two worlds, a clash between Britain’s burgeoning industrial capitalism and Qing China’s ancient, self-sufficient imperial system. It’s a story about economics, culture, and two completely irreconcilable views of how the world should work.

The Great Silver Drain: Britain’s China Problem

For centuries, Europe had been fascinated by China. Its silks, porcelain, and, most importantly, its tea were in high demand. By the late 18th and early 19th centuries, tea had become a national obsession in Britain, a staple of daily life from the drawing rooms of the aristocracy to the cottages of the working class.

There was just one massive problem: China didn’t want anything Britain produced. The Qing Empire, under emperors like Qianlong, viewed itself as the “Middle Kingdom”—the glorious center of civilization. All other nations were considered inferior “barbarians.” The Qing economy was vast and largely self-sufficient. They had little use for the heavy woolen textiles and rudimentary industrial goods Britain had to offer.

Trade was heavily restricted through the rigid Canton System. Foreign merchants were permitted to trade only in the port of Canton (modern Guangzhou), were confined to a small district known as the Thirteen Factories, and could only deal with a government-approved monopoly of Chinese merchants called the Cohong. This system was designed to maximize profit for China while minimizing foreign influence and cultural contamination.

The result was a staggering trade deficit. To pay for all that tea, Britain had only one thing the Chinese market would accept: silver. Shipload after shipload of silver bullion sailed from London to Canton, causing a massive and unsustainable “silver hemorrhage.” For a Britain operating on a mercantilist worldview—where national wealth was measured by its holdings of precious metals—this was an economic catastrophe in the making.

A ‘Diabolical’ Solution: The Triangle Trade

Britain needed to find a product that the Chinese would buy, something to reverse the silver drain. They found it in opium.

The British East India Company (EIC), which held a monopoly on British trade in the East, began to cultivate vast fields of poppies in its newly conquered territories in India. They processed the poppies into raw opium and devised a cynical but brilliant triangular trade system:

- Step 1: Opium, grown and processed in British India, was sold to private traders and smugglers (allowing the EIC to deny direct involvement).

- Step 2: These smugglers flooded the Chinese coast with the drug, selling it to Chinese black marketeers in exchange for silver.

- Step 3: This “new” silver was then used by the EIC in Canton to purchase tea and other Chinese goods for export back to Britain.

The plan worked spectacularly. By the 1830s, the flow of silver had completely reversed. Silver was now pouring out of China and into British coffers. Britain had solved its trade deficit, but at a horrifying cost to China. Opium addiction created a widespread social crisis, decimating communities and draining the empire’s treasury.

A Clash of Civilizations: Diplomacy, Law, and the Kowtow

The economic conflict was compounded by a complete inability to communicate on equal terms. The two empires operated on fundamentally different principles of diplomacy and law.

The Chinese Worldview: China’s Sinocentric system did not recognize other nations as sovereign equals. Foreign emissaries were seen as tribute-bearers, expected to perform the “kowtow”—a full prostration of three kneelings and nine head-bows—to acknowledge the emperor’s supreme status as the Son of Heaven. The famous Macartney Mission of 1793, a British attempt to establish direct diplomatic relations, failed spectacularly over this very issue. The Qianlong Emperor’s reply to King George III was famously dismissive: “Our Celestial Empire possesses all things in prolific abundance… We have no need for your country’s manufactures.”

The British Worldview: Britain, flush with the power of the Industrial Revolution and a growing global empire, was pioneering a new world order based on free trade, international law, and the sovereign equality of nations. They demanded the right to have an ambassador in Beijing, to trade freely in multiple ports, and for their citizens to be subject to British law, not Chinese law (a concept known as extraterritoriality).

These two worldviews could not coexist. To China, Britain’s demands were the absurd requests of an upstart barbarian. To Britain, China’s refusal to negotiate was an archaic, insulting barrier to “progress” and profit.

The Spark That Ignited the Powder Keg

By 1839, the Daoguang Emperor had seen enough. Alarmed by the social devastation and the economic drain caused by the opium trade, he appointed an imperial commissioner, Lin Zexu, to eradicate the problem.

Lin was a man of immense integrity and determination. Arriving in Canton, he took decisive action. He blockaded the foreign traders in their factories and demanded they surrender their entire stock of opium. After a six-week standoff, the British Superintendent of Trade, Charles Elliot, relented. Lin Zexu then had over 20,000 chests of opium—roughly 1,400 tons—publicly destroyed in a dramatic show of imperial power.

In China, Lin was a hero. In London, his actions were portrayed as an outrageous affront. The debate in Parliament was fierce, but the pro-war faction, led by Foreign Secretary Lord Palmerston, framed the issue masterfully. This wasn’t about selling drugs; it was about the seizure of £2 million worth of British private property, an insult to the dignity of the Crown, and the “barbaric” Chinese refusal to engage in free trade. The war, they argued, was necessary to defend British honor and commercial interests.

The outdated Chinese military was no match for Britain’s steam-powered gunboats and modern army. The war was a one-sided affair, culminating in the 1842 Treaty of Nanking. This, the first of the “unequal treaties”, forced China to pay a massive indemnity, cede Hong Kong to Britain, and open five new ports to foreign trade. The Canton System was shattered.

Conclusion: The War for a New World Order

So, was the First Opium War about opium? Yes, but only in the way a bar fight is about a spilled drink. The spilled drink starts the brawl, but the real causes are the underlying tensions, rivalries, and egos that were already present.

Opium was the perfect commodity to pry open the closed Chinese market and reverse a ruinous trade deficit. Lin Zexu’s destruction of that commodity provided the perfect political pretext for a war Britain was already ideologically and economically primed to fight. The war was, at its core, a violent, tragic collision fought to replace China’s ancient, self-contained world order with Britain’s new global vision of free trade, diplomatic access, and, ultimately, imperial dominance.