A World Turned Upside Down

Celebrated across Europe, primarily in France, from the 12th to the 16th centuries, the Feast of Fools was a sanctioned festival of misrule centered around the New Year. Typically held between Christmas and Epiphany—often on the Feast of the Circumcision (January 1st)—it belonged mainly to the junior clergy: the subdeacons, choirboys, and other church functionaries who occupied the bottom rung of the ecclesiastical ladder.

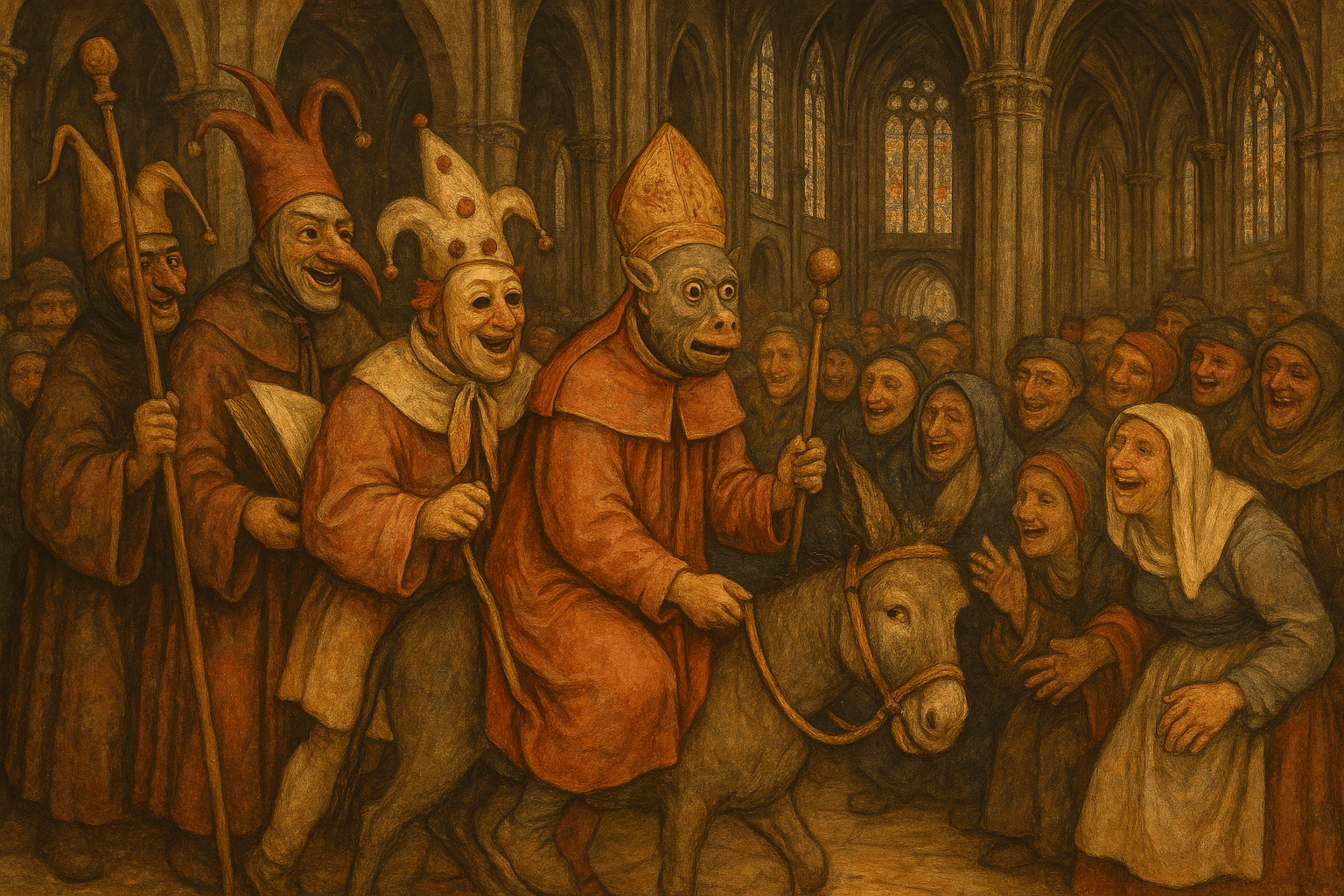

For this one day, the rigid hierarchy of the Church was inverted. The powerless became the powerful. The central act of the festival was the election of a “Lord of Misrule”, or more commonly, a “Boy Bishop” or “Abbot of Fools.” A low-ranking subdeacon or even a choirboy would be “elected” to mock the authority of the actual bishop. Dressed in full, often ill-fitting, episcopal regalia, he would preside over the day’s chaotic proceedings with a mock seriousness that only heightened the absurdity.

The festivities would then spill into the church itself, leading to a parody of the most sacred of Christian rituals: the Mass.

Blasphemy or Blowing Off Steam?

The “services” conducted during the Feast of Fools were a masterclass in satirical inversion. The participants would:

- Wear their priestly vestments inside-out or backwards.

- Hold their prayer books upside down and pretend to read gibberish.

- Sing nonsensical or obscene lyrics to the tunes of sacred hymns.

- Instead of the dignified call-and-response of the liturgy, they would make animal noises. The traditional “Ite, missa est” (Go, the Mass is ended) might be replaced by three loud donkey brays.

- As mentioned, they would burn foul-smelling objects in the censers and eat and drink on the altar itself.

The chaos wasn’t confined to the cathedral walls. After the mock service, the revellers would often burst into the streets, leading a riotous procession. They would sing, dance, cross-dress, and perform satirical plays, mocking not only their clerical superiors but secular authorities as well. It was a day of total, unadulterated liberty.

A horrified letter from the Faculty of Theology at Paris in 1445 perfectly captures the scene:

“Priests and clerks may be seen wearing masks and monstrous visages at the hours of office. They dance in the choir dressed as women, panders or minstrels. They sing wanton songs. They eat black puddings at the horn of the altar while the celebrant is saying mass. They play at dice there. They cense with stinking smoke from the soles of old shoes. They run and leap through the church, without a blush at their own shame.”

The Purpose of the Madness

To our modern sensibilities, this all sounds deeply sacrilegious. So why did the powerful church authorities tolerate—and in the early days, even participate in—such a spectacle? The answer is complex, lying at the intersection of psychology, religion, and social control.

The most common theory is that the Feast of Fools acted as a social “safety valve.” The subdeacons and junior clergy lived lives of poverty and strict obedience, often serving arrogant and wealthy superiors. The feast allowed them to vent their frustrations in a controlled, temporary environment. By permitting the world to be turned upside down for a single day, the authorities ensured it would remain right-side-up for the other 364. The temporary chaos reinforced the daily order.

There was also a theological justification, rooted in the words of the Magnificat (Luke 1:52): “He has brought down the mighty from their thrones and has lifted up the humble.” The feast was a living reminder that all earthly power is temporary and that in the eyes of God, the last shall be first. It was a performative act of humility for the powerful, who had to endure being mocked by their inferiors.

Finally, the festival likely had pre-Christian roots, echoing the Roman festival of Saturnalia. During Saturnalia, a winter solstice celebration, slaves were served by their masters, gambling was permitted, and a “King of Saturnalia” presided over the fun, similar to the Lord of Misrule. The Feast of Fools was, in many ways, the Christian successor to this ancient tradition of winter role-reversal.

The Inevitable Backlash

As the centuries wore on, the official tolerance for the Feast of Fools began to fray. What was once seen as a harmless release of tension was increasingly viewed as genuinely blasphemous and a threat to public order.

Church councils began to condemn the practice with growing frequency. The Council of Basel in 1431 officially forbade it, though the tradition proved difficult to stamp out. The 1445 letter from Paris shows that the hierarchy was losing its patience. The line between sanctioned fun and outright sacrilege was becoming too thin.

The final blow came with the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century. For reformers like Martin Luther and John Calvin, the Feast of Fools was not a quirky tradition; it was definitive proof of the corruption, decadence, and godlessness of the Catholic Church. In the face of such criticism, the Catholic Church itself, during its own Counter-Reformation, sought to clean house, promoting greater decorum, piety, and control. The wild, unpredictable Feast of Fools had no place in this new, more austere world.

By the end of the 16th century, the feast had largely vanished, surviving only in fragmented folk traditions. The sanctioned chaos was over. Yet, its memory serves as a vital reminder that the medieval world was not the monolithic, perpetually grim, and pious society it is often imagined to be. It was a place of complexity, contradiction, and profound human impulses, where for one wild day each year, even a fool could be king.