The Etruscan Obsession with Fate

The ancient civilization of Etruria, which flourished in modern-day Tuscany from the 8th to the 1st century BCE, possessed a unique and fatalistic worldview. They believed their society had a divinely allotted lifespan and that the will of the gods permeated every aspect of the natural world. This intricate system of belief was codified in a collection of sacred texts known as the Disciplina Etrusca. These books, now lost to history but described by Roman writers like Cicero, were a complete guide to understanding the divine will. They covered everything from interpreting lightning strikes (libri fulgurales) to proper ritual procedures (libri rituales) and, most famously, the art of reading entrails (libri haruspicini).

For the Etruscans, the future was not something to be passively awaited. It was a series of signs to be actively sought out and interpreted. A public project, a declaration of war, or even a personal business venture required divine consultation. The haruspex was the essential intermediary in this dialogue between mortals and gods, a highly respected figure whose skills were honed through years of rigorous training.

The Art of the Harupex: A Celestial Map in Flesh

The ritual of haruspicy was a solemn and precise affair. After a carefully selected animal, typically a sheep, was sacrificed, the haruspex would meticulously examine its internal organs. While the heart, lungs, and intestines were inspected, the liver (iecur) held the highest importance. Its rich blood supply and vital role in life made it the perfect vessel for divine communication.

The haruspex wasn’t just looking for a simple “good” or “bad” sign. The examination was incredibly detailed. They would analyze:

- Size and Shape: Was the liver swollen, shrunken, or misshapen?

- Color and Texture: Was it pale, dark, smooth, or grainy?

- Markings and Blemishes: Any spots, holes, or growths were considered significant omens.

- Key Features: A particular protrusion called the caput iocineris (“head of the liver”) was critically important. Its absence was a catastrophic omen. The famous warning given to Julius Caesar before his assassination—”Beware the Ides of March”—came from a haruspex named Spurinna, who had reportedly observed a sacrificial animal with no heart or, in another version of the story, a liver without a caput iocineris.

The liver was conceptually divided into two main parts: the pars familiaris (the part concerning the questioner and their allies) and the pars hostilis (the part concerning their enemies). A defect on the pars familiaris was a dire warning, while a blemish on the pars hostilis could be interpreted as a positive sign, indicating misfortune for one’s adversaries.

The Liver of Piacenza: A Bronze Age Textbook

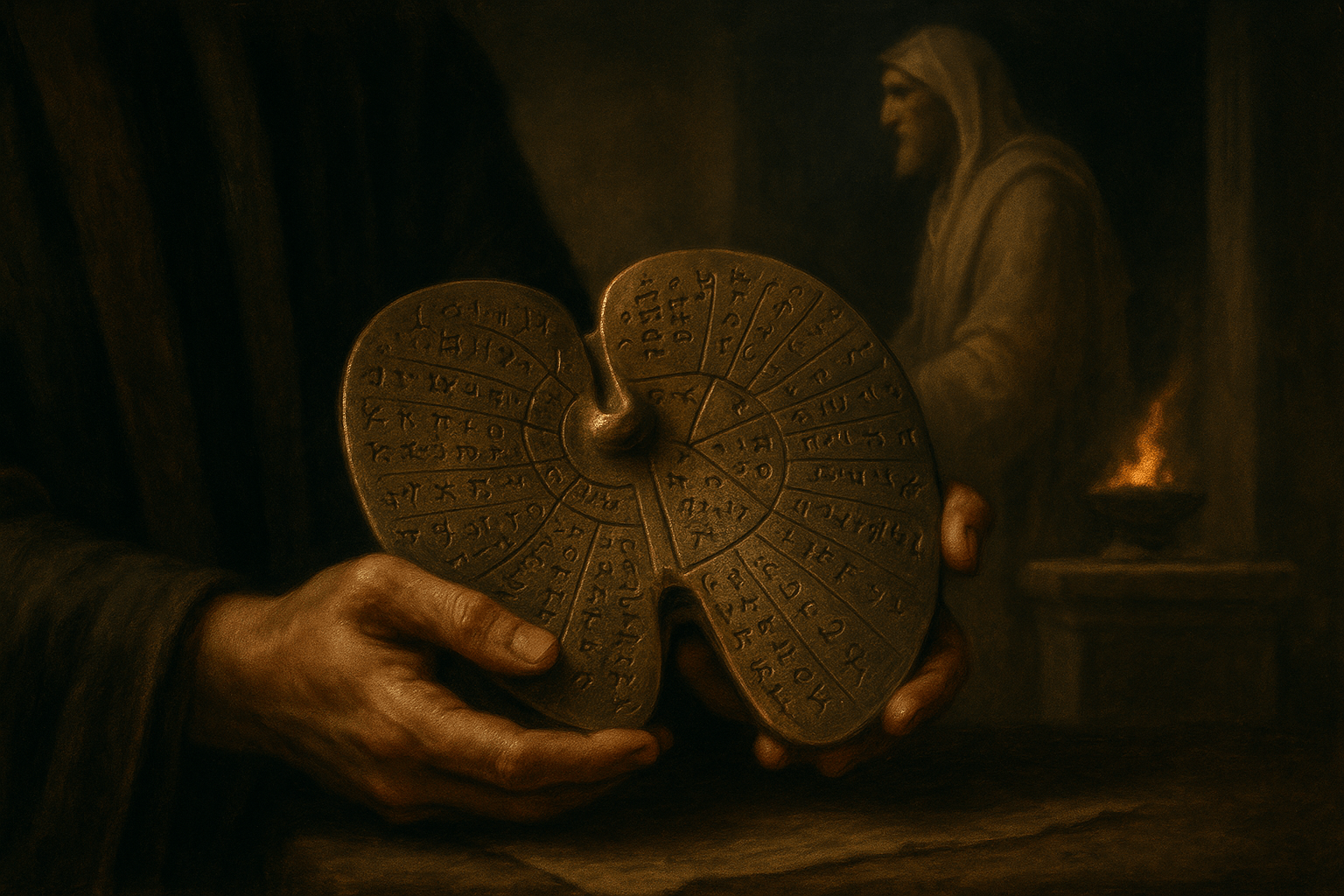

How could a haruspex possibly memorize the meaning of every potential abnormality and its precise location on the liver? The answer lies in one of the most remarkable artifacts to survive from the Etruscan world: the Liver of Piacenza.

Discovered by a farmer in a field in 1877, this life-sized bronze model of a sheep’s liver is, in essence, a divinatory textbook. Dating to around 100 BCE, it served as a three-dimensional guide for apprentice priests, mapping the celestial and divine world onto the organ’s anatomy.

The bronze liver is a masterpiece of complex theology. Its surface is meticulously subdivided into regions, with the outer rim divided into 16 sections, corresponding to the 16 houses of the Etruscan heavens. Within these regions and across the liver’s surface are inscribed the names of over 40 Etruscan deities. Each section of the liver was the domain of a specific god or goddess.

In practice, a haruspex would orient the real liver (and their bronze model) according to the cardinal directions, aligning it with the sky. If an anomaly—a lump, a hole, a discoloration—was found on a particular part of the real liver, the priest would consult their bronze map. The location of the blemish corresponded to a specific divine region. If the flaw appeared in the section marked for Tinia (the Etruscan equivalent of Jupiter/Zeus), it was Tinia who was sending the message. The nature of the flaw would then determine if the god was angry, pleased, or offering a specific warning.

This ‘cosmological liver’ transformed a biological organ into a sacred map, turning a visceral inspection into a systematic reading of a divine message.

From Etruria to the Roman Empire

The Romans were both fascinated by and wary of their Etruscan neighbors, but they held the Disciplina Etrusca in extremely high regard. As Rome’s power grew and Etruria’s waned, the Romans eagerly adopted the art of haruspicy. The Roman Senate officially established a “College of Haruspices” to preserve and practice this Etruscan knowledge.

Throughout the Roman Republic and into the Empire, haruspices were consulted before major battles, the founding of new cities, and during times of crisis like plagues or perceived divine anger. Roman generals, politicians, and emperors all kept haruspices in their retinue. The practice was so deeply embedded that it survived for centuries, only truly fading with the rise of Christianity, which actively suppressed it as a pagan superstition.

Haruspicy offers a profound window into the Etruscan mind. It was far more than simple fortune-telling. It was an institutionalized system for maintaining order between the human and divine worlds, a way of understanding a universe that was alive with sacred power. By looking into the liver of a sheep, the Etruscan haruspex was attempting to read the very mind of the gods, decoding a message written not in stone or on a scroll, but in flesh and blood.