A Watery World: The Old Fenland

Before its transformation, the Great Level of the Fens covered nearly 1,500 square miles across what is now Cambridgeshire, Lincolnshire, and Norfolk. It was a immense, low-lying basin, seasonally flooded by the rivers that flowed into it but struggled to find their way out to the sea. This wasn’t a barren swamp, however. It was a dynamic and incredibly rich ecosystem, teeming with life.

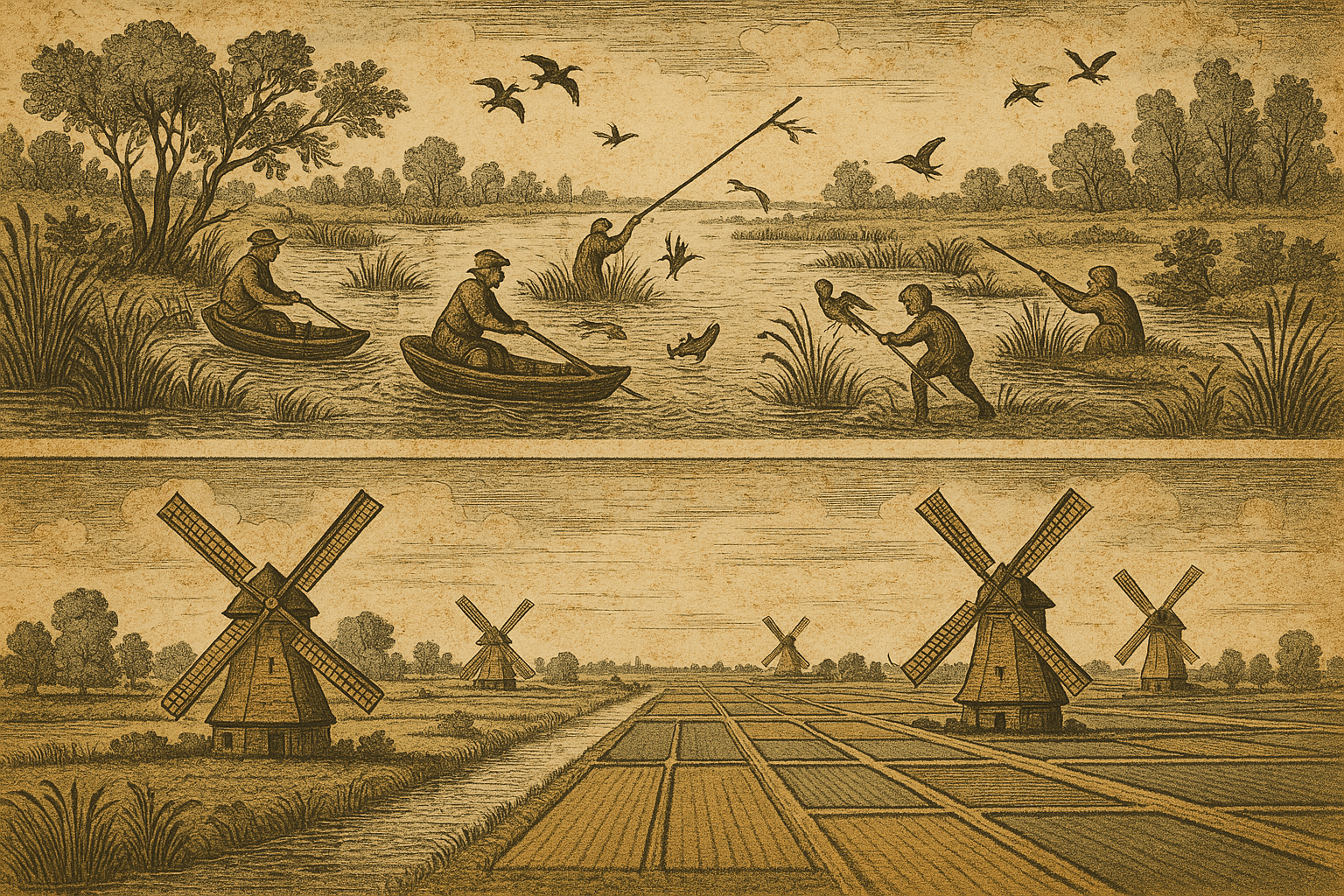

The local inhabitants, sometimes called “Fen Slodgers”, had forged a unique culture perfectly adapted to their environment. Their economy was based on the commons—shared resources that belonged to all. They:

- Fished for pike and caught astronomical numbers of eels, a staple food and currency.

- Fowled for ducks and geese, their nets and decoys providing food for markets as far as London.

- Harvested reeds and sedge for thatching and fuel.

- Grazed hardy cattle on the summer pastures that emerged as floodwaters receded.

This was a life of isolation and self-sufficiency, viewed with suspicion by outsiders who saw the Fens as a gloomy, miasmatic wasteland. To the 17th-century mind, obsessed with order and agricultural improvement, this untamed landscape was not a resource but a challenge—an affront to God and Crown that needed to be “recovered.”

The Vision of an Agricultural Empire

The impetus for drainage came from a powerful alliance of the Crown and capital. King Charles I, locked in a power struggle with Parliament and desperate for funds, saw the Fens as a source of wealth. By granting a royal charter to drain the land, he could claim a massive portion of the reclaimed territory for the Crown, sell it off, and bypass parliamentary taxes.

He found willing partners in a group of wealthy investors known as the “Adventurers”, led by Francis Russell, the 4th Earl of Bedford. Their motive was pure profit. They would finance the incredibly expensive drainage works in exchange for being granted tens of thousands of acres of what they believed would become the richest farmland in England. The vision was to convert a common wetland into a private, agricultural powerhouse. To achieve this, they needed someone who knew how to conquer water.

Enter the Dutch Master: Cornelius Vermuyden

England looked to the Netherlands, a nation literally built on reclaimed land. The Dutch had spent centuries creating their famous polders, turning sea and marsh into productive ground. The Adventurers hired the best: Cornelius Vermuyden, a Dutch engineer who had already undertaken smaller drainage projects in England.

p>Vermuyden’s approach was radical and bold. Instead of working with the Fens’ meandering watercourses, he proposed to overwhelm them with brute Dutch logic. His plan involved creating a network of massive, dead-straight artificial rivers, or drains, to bypass the old, clogged channels and speed the flow of water directly to the sea. His masterwork was a twenty-one-mile-long channel cutting straight across the heart of the Fens. When this proved insufficient, he dug a second, parallel channel, creating the “Old Bedford River” and the “New Bedford River” (or “Hundred Foot Drain”), which remain defining features of the landscape today. Supported by a complex system of sluices, gates, and embankments, it was an engineering marvel of its time.

The Revolt of the Fen Tigers

For the financiers and the Crown, drainage was “improvement.” For the thousands of Fenlanders, it was an act of war. The project wasn’t just reshaping the land; it was obliterating their entire way of life. The draining of the commons meant:

- The rivers and meres that provided fish disappeared.

- The reedbeds that supplied thatch and fuel dried out and were ploughed up.

- The summer grazing for their animals was enclosed and given to the Adventurers.

In a stroke, their skills, tools, and traditions were rendered obsolete. Their response was fierce, earning them the nickname “Fen Tigers.” They engaged in a prolonged guerrilla campaign of sabotage and resistance. They broke down the new embankments, filled in the drains at night, destroyed sluice gates, and attacked the gangs of workmen. During the English Civil War, the breakdown of royal authority allowed the Fenlanders to reclaim much of their land, destroying years of Vermuyden’s work. But the project was restarted after the war, and this time, the rebellion was systematically crushed. The Fen Tigers fought for their homes and livelihoods, but they could not stop the relentless march of capital and engineering.

A Transformed Landscape: Success and Unforeseen Consequences

By the end of the 17th century, the project was largely complete. The Fens had been transformed into a vast, flat expanse of dark, fertile soil. The scheme was, from an agricultural perspective, a stunning success. But this success came with a profound and ironic twist.

The Fenland soil was primarily peat—a spongy accumulation of partially decayed vegetation, saturated with water. Once the water was drained away, the peat began to dry out. Exposed to the air, it oxidized and compacted. The very ground itself began to shrink and disappear. As a result, the land level of the drained Fens started to sink dramatically.

This created a catastrophic problem: the newly created farmland soon fell below the level of the rivers that were supposed to drain it. Gravity, Vermuyden’s partner, had become the enemy. Water could no longer flow out; it had to be lifted up into the drainage channels. Initially, this was done with scores of windpumps, another Dutch innovation. Later, in the 19th and 20th centuries, these were replaced by giant, coal-fired steam engines and finally, the diesel and electric pumps that work tirelessly today.

The dramatic effect of this peat shrinkage is visualized at the Holme Fen Posts. In 1851, a metal post was driven through the peat into the stable clay below, its top level with the ground. Today, that same post towers nearly 13 feet above the surrounding fields, a stark monument to a sinking landscape. The draining of the Fens was not a one-time event; it began a perpetual, energy-intensive battle to keep the water out of a land that is now, in many places, well below sea level.

The story of the Fens is a powerful saga of transformation, conflict, and consequence. It is a tale of engineering genius and ecological shortsightedness, of the creation of agricultural wealth at the cost of a unique culture, and of a landscape forever remade by human hands, now dependent on constant vigilance to survive.