A Kingdom on the Brink

Before the storm, monasticism was deeply woven into the fabric of English life. Monks and nuns were a familiar sight, and their daily prayers were believed to benefit the entire kingdom. Their institutions were vast landowners, controlling perhaps a quarter of all cultivated land in England and Wales. They were major employers, running farms, mines, and fisheries. Their libraries preserved priceless manuscripts, their workshops produced stunning art, and their infirmaries were the closest thing to public hospitals.

However, by the 1530s, criticism was growing. Reformist thinkers like Erasmus had long accused some houses of corruption, wealth, and a lack of spiritual discipline. While many monasteries remained devout and well-run, others had undoubtedly become complacent, more concerned with their role as powerful landlords than as spiritual shepherds. This provided a convenient moral justification for what was to come.

The King’s Great Matter and a Hunger for Wealth

The primary catalyst for the Dissolution was not religious reform, but royal politics. Henry VIII was desperate for a male heir and had fallen in love with Anne Boleyn. He needed his marriage to his first wife, Catherine of Aragon, annulled. When Pope Clement VII refused, Henry took the unprecedented step of breaking with the Roman Catholic Church. The 1534 Act of Supremacy declared Henry the Supreme Head of the Church of England, severing a thousand years of religious history.

This break created two pressing problems for the king:

- Loyalty: The monasteries were international institutions. Abbots and priors owed their ultimate allegiance to the heads of their orders in France, Italy, or Spain—and by extension, to the Pope. They represented a potential fifth column, a powerful network of opposition loyal to Rome. Suppressing them meant neutralizing a significant threat to Henry’s new-found religious authority.

- Money: The Crown was perpetually short of cash. Wars with France and Scotland were expensive, and Henry’s court was lavish. The Church, on the other hand, was fantastically wealthy. The Dissolution was, at its heart, the largest asset-stripping operation in English history.

Cromwell’s Calculated Campaign

The man tasked with executing this colossal undertaking was Thomas Cromwell, a brilliant and ruthless administrator who served as Henry’s chief minister. Cromwell’s approach was methodical and brutally efficient.

Step 1: The Survey – Valor Ecclesiasticus

In 1535, Cromwell commissioned a comprehensive survey of all church property in England and Wales. Known as the Valor Ecclesiasticus (“the value of the church”), it was a Domesday Book of the Tudor age. Commissioners meticulously documented the assets, lands, and income of every single religious institution. The final report revealed their staggering wealth, providing Cromwell with a detailed ledger of the prize to be seized.

Step 2: The Justification – The Visitations

Next, Cromwell dispatched commissioners to “visit” the monasteries and report on their moral and spiritual state. Their goal was not to conduct an impartial investigation, but to find dirt. Abbots were interrogated, and monks were encouraged to inform on each other. The resulting reports, known as the Compendium Compertorum, were a lurid collection of alleged sins, from financial mismanagement and idolatry to sexual immorality. While likely exaggerated, they provided the parliamentary propaganda needed to justify closure.

Step 3: The Acts of Dissolution

Armed with financial data and moral justification, the process began. The First Suppression Act of 1536 targeted the smaller houses with an annual income of less than £200. It was framed as a “reform”—moving monks from corrupt, small houses to larger, more virtuous ones. Of course, this was a fiction. The larger houses were next in line.

Resistance and Ruin

The closure of local monasteries, which provided essential charity and employment, provoked a furious backlash. In the autumn of 1536, a massive popular uprising known as the Pilgrimage of Grace erupted in Northern England. Tens of thousands of protesters, led by the lawyer Robert Aske, marched under the banner of the Five Wounds of Christ, demanding the restoration of the monasteries and a halt to Henry’s Reformation.

Henry brutally suppressed the rebellion, executing its leaders and ending any hope of a reversal. If anything, the uprising hardened his resolve. The larger monasteries, some of whose abbots had supported the Pilgrimage, were now dealt with. From 1537 onwards, abbots were “persuaded” by threats, pensions, and intimidation to “voluntarily” surrender their houses to the Crown. Those who resisted, like the abbots of Glastonbury, Reading, and Colchester, were executed for treason.

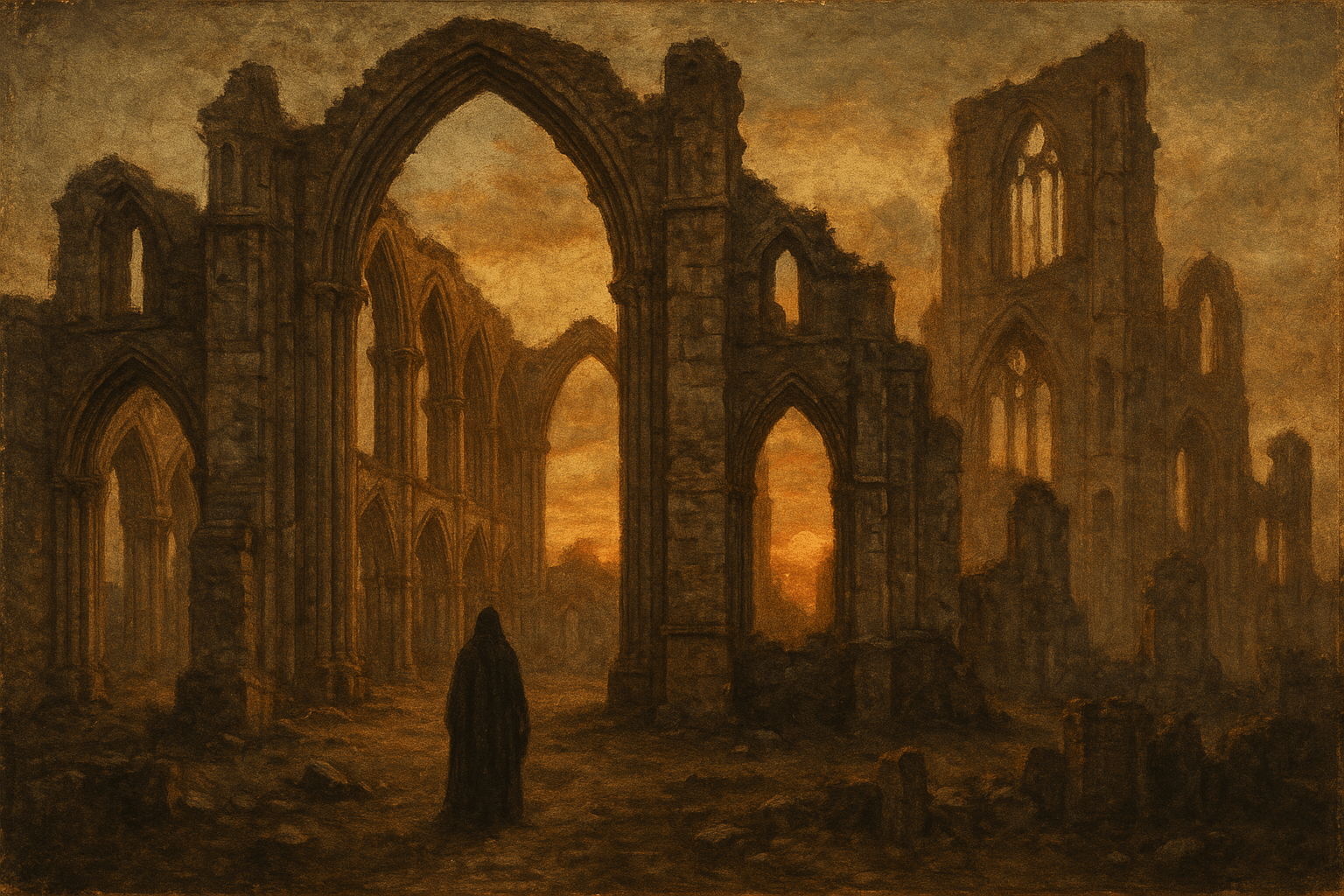

The physical destruction was swift and total. The king’s men stripped the lead from the roofs, melted down the bells, smashed the stained glass, and seized anything of value. Libraries that had taken centuries to assemble were scattered or burned. The buildings themselves were either sold to local gentry to be converted into country mansions or used as a free quarry for building materials, leaving the iconic, skeletal ruins that still haunt the English countryside today.

A Transformed Society

The Dissolution of the Monasteries reshaped England forever. The immediate consequence was a massive redistribution of wealth. Monastic lands were sold off, primarily to the nobility and rising gentry. This created a new class of landowner whose status and fortune were directly tied to the success of the Tudor dynasty and the English Reformation, ensuring there would be no turning back to Rome.

For the poor, the social impact was devastating. The closure of the monasteries eliminated a crucial safety net. With no alms, no monastic hospitals, and no places of sanctuary, vagrancy and poverty increased, problems the government would struggle with for generations.

Culturally, the loss was incalculable. Thousands of illuminated manuscripts, religious relics, and works of art were destroyed. The great abbey churches, some of the finest examples of Gothic architecture in Europe, were reduced to rubble. But from this destruction, a new England emerged—one where the power of the state was supreme, where a new aristocracy held sway, and where the landscape itself bore the silent, stone scars of a king’s ruthless ambition.