In the wake of the Greco-Persian Wars, a collective sigh of relief echoed across the Aegean. The mighty Persian Empire had been repelled, its ambitions shattered on the shores of Marathon, in the straits of Salamis, and on the fields of Plataea. But this victory was hard-won, and the fear of a Persian return lingered like a ghost at the feast. To safeguard their newfound freedom, the Greek city-states, minus a wary Sparta and its allies, forged a new pact in 478 BCE: the Delian League.

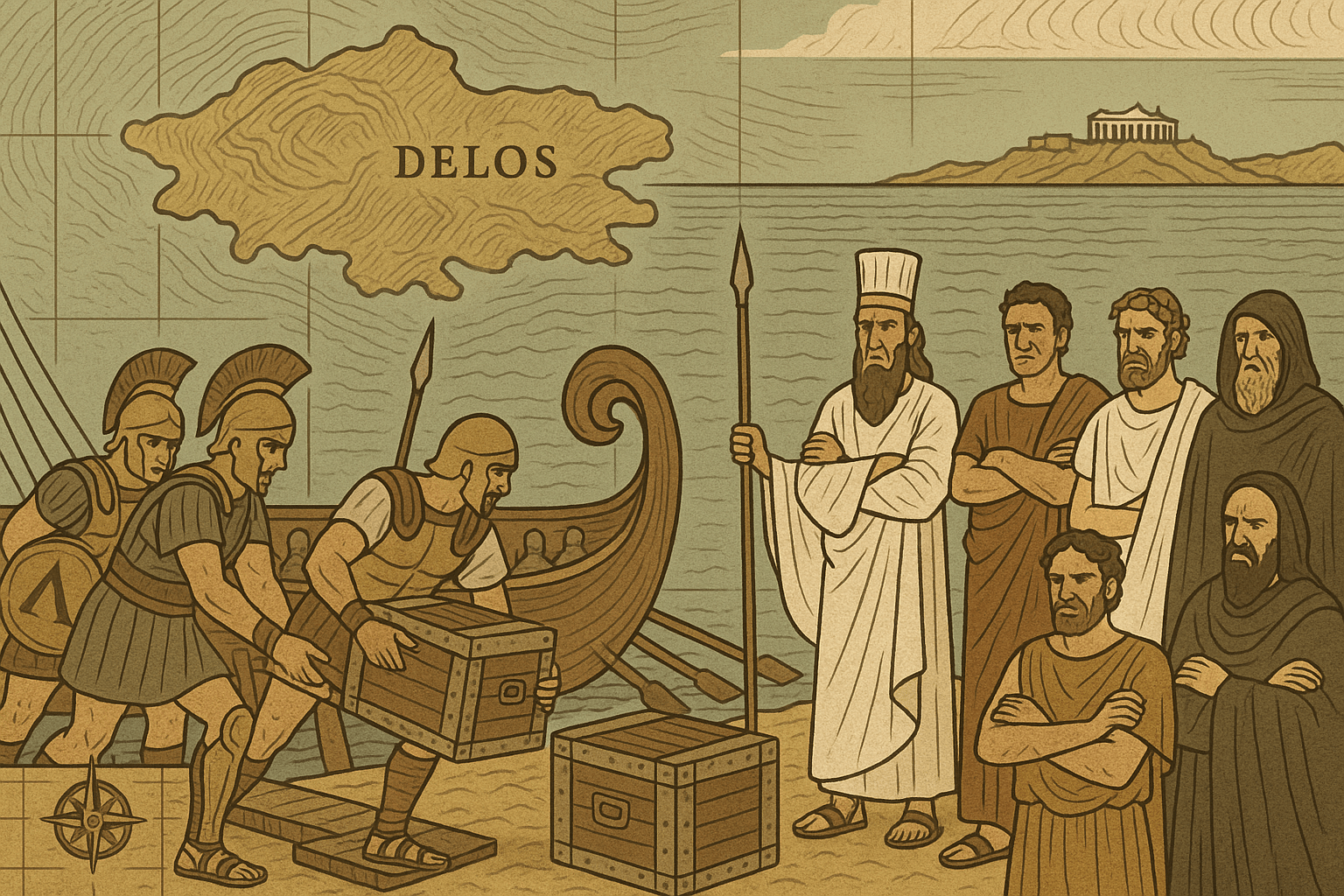

Its initial purpose was noble and clear: a voluntary alliance for mutual defense. The league’s headquarters and, crucially, its treasury were established on the sacred and politically neutral island of Delos, home to the sanctuary of Apollo. Members pledged to contribute either ships and men or a monetary payment, the phoros, to a common fund. It was a joint savings account for security, with all members as equal partners. Or so it seemed.

The Rise of the Hegemon

From the outset, one state was more equal than others: Athens. With its peerless navy, which had been the linchpin of the victory at Salamis, Athens was the League’s natural leader, or hegemon. In the early years, this arrangement worked. The League, under Athenian command, successfully liberated remaining Greek cities in Ionia and swept the Persians from the Aegean.

However, a subtle but critical shift began to occur. Many smaller city-states, lacking the resources or inclination to build and man warships, found it easier to simply pay the phoros. Athens, more than happy to accept the cash, used it to build and maintain its own fleet. With each passing year, the Athenian navy grew stronger, while the navies of its “allies” shrank or vanished entirely. The allies were effectively outsourcing their defense to Athens, a decision that would have profound and irreversible consequences.

The first signs of trouble emerged when states tried to leave the alliance. The island of Naxos, around 471 BCE, decided it had had enough. Citing the diminished Persian threat, it attempted to secede. Athens responded not with diplomacy, but with force. The Naxians were besieged, conquered, and forced back into the League, their ships confiscated and their walls torn down. They were now a tribute-paying subject. The mask was beginning to slip. What began as a voluntary club was starting to look like a protection racket.

The Fateful Move of 454 BCE

The final, undeniable transformation from alliance to empire came in 454 BCE, with a single, audacious decision. The architect of this move was the great Athenian statesman, Pericles. Citing the ongoing (and failing) Athenian military expedition in Egypt and the theoretical vulnerability of Delos to pirates or a Persian raid, Pericles proposed that the League’s treasury be moved from its neutral home on Delos to the safest place he could imagine: the Acropolis of Athens.

The pretext was security; the reality was power. Moving the treasury was the political equivalent of one person in a joint venture moving all the shared funds into their private account. The allies protested, but what could they do? For decades, they had been paying Athens to maintain a navy, and now that very navy was the instrument of their own subjugation. They had no military means to resist Athens’ will.

The transfer of the treasury was dripping with symbolism. The wealth of the Greek world was taken from the sanctuary of the pan-Hellenic god Apollo and placed in the temple of Athena, the patron goddess of Athens. The message was unmistakable: the League’s resources no longer belonged to the Greeks; they belonged to Athens.

From Mutual Fund to Athenian Slush Fund

With the treasury secure within its own walls, Athens no longer felt the need to maintain even the pretense of an equal partnership. The phoros, the contributions of the allies, became tribute in all but name, financing not just the navy but the glorification of Athens itself.

This is the moment that funded Athens’ “Golden Age.” The allies’ silver paid the salaries of Athenian public officials and jurors, fueling its radical democracy. Most famously, it was used to finance Pericles’ ambitious public building program, a project that would immortalize Athens and give the world its most iconic structures.

When the Parthenon, the Propylaea, and the other magnificent temples rose on the Acropolis, they were built with League money. As Plutarch reports, Pericles’ opponents were outraged, claiming the people of Athens had lost their honor by “gilding and bedizening our city, which, for all the world like a wanton woman, adds to her wardrobe the cost of precious stones and statues and temples worth a thousand talents.”

Pericles’ response was chilling in its imperial logic. He argued that as long as Athens provided the defense it had promised, the allies had no right to audit the books.

“They do not give us a single horse, or a soldier, or a ship, do they? All they supply is money… It is no more than fair that after having provided for the war and made all secure, we should apply the surplus to works that will bring us glory for all time.”

The deal had been rewritten. The allies paid for protection, and Athens could do whatever it wanted with the money. Allies had officially become subjects.

The Road to Ruin

The relocation of the treasury and the subsequent use of its funds solidified Athenian dominance, but it also sowed the seeds of its destruction. The resentment among the subject-allies festered. Across the Greek world, Sparta and its Peloponnesian League watched with growing alarm. They saw Athenian power not as a shield against Persia, but as a tyrannical force threatening the autonomy of all Greeks.

Sparta could now credibly position itself as the “liberator of Greece”, a rallying cry that many of Athens’ disgruntled subjects were eager to hear. The immense wealth Athens extracted from its empire allowed it to fight a long and costly war, but the imperial arrogance that began with the transfer of the treasury ultimately led directly to the devastating Peloponnesian War (431-404 BCE).

The story of the Delian Treasury is a timeless lesson in how power corrupts. What was born from a desire for collective security morphed, step by step, into an instrument of oppression. The single administrative act of moving a treasury from one island to another marked the point of no return, turning allies into subjects and setting the Greek world on a collision course with itself.