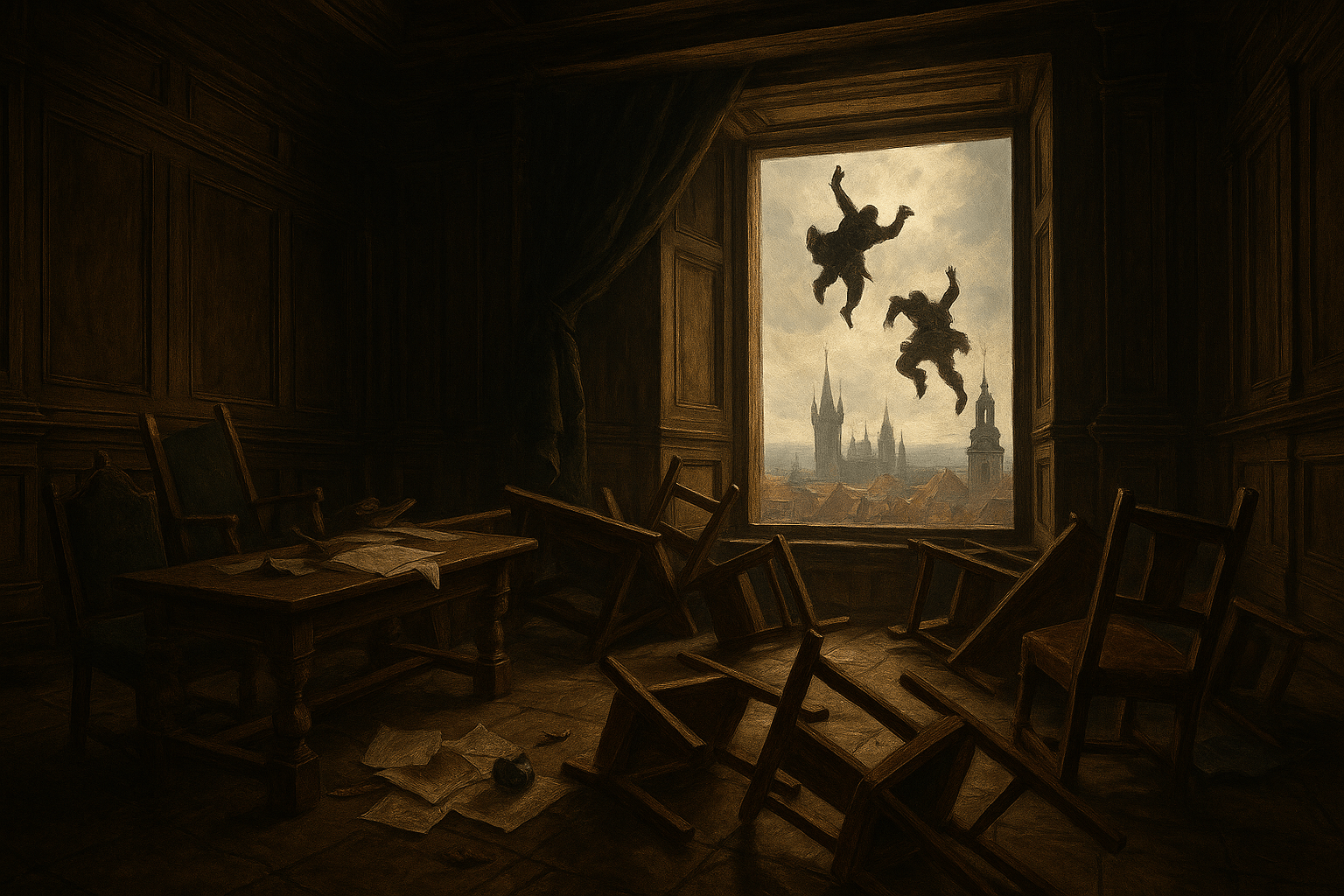

These were not random acts of mob violence. The three famous Defenestrations of Prague were calculated outbursts of fury, each tearing at the religious and political fabric of the era. They were symbolic rejections of authority that sparked decades of warfare and reshaped the continent. Let’s look out the window, so to speak, at these pivotal moments in history.

The Spark of the Hussite Wars: The First Defenestration of 1419

To understand the first defenestration, we must first understand the firebrand preacher Jan Hus. A century before Martin Luther, Hus was a Bohemian religious reformer who criticized the corruption of the Catholic Church, advocating for services in the vernacular language and for the laity to receive both bread and wine during communion (a practice known as Utraquism). For his troubles, he was declared a heretic and burned at the stake in 1415.

His death did not silence his ideas; it turned him into a martyr and galvanized his followers, the Hussites. Tensions simmered for four years until they boiled over on July 30, 1419. A radical Hussite preacher, Jan Želivský, led a massive procession through the streets of Prague, marching to the New Town Hall (Novoměstská radnice) to demand the release of several Hussite prisoners.

When the procession arrived, the anti-Hussite town councillors refused the demand and, according to some accounts, a stone was thrown from the hall at the crowd. Enraged, the mob stormed the building. They seized the burgomaster, the judge, and several Catholic councillors. In a furious act of rebellion, they hurled the officials from the high windows.

Below, the crowd waited with pikes and spears. None of the officials survived the fall or the mob that met them. This brutal act is unanimously seen as the immediate trigger for the Hussite Wars (1419-1434), a series of brutal conflicts that pitted the Bohemian Hussites against the might of the Holy Roman Emperor and the Pope, who launched multiple crusades against them.

An Echo of Discontent: The Second Defenestration of 1483

While less famous than its predecessor or successor, the Second Defenestration demonstrates that window-tossing had become an established part of the Bohemian political playbook. By 1483, the Hussite Wars were long over, and a fragile religious peace existed between the Utraquist Hussites and the Catholics under King Vladislaus II.

However, Catholic authorities, with the quiet backing of the king, sought to regain control and roll back the religious and political freedoms the Hussites had won. Rumors swirled of an impending Catholic coup in Prague, designed to eliminate their rivals and install a purely Catholic administration.

Rather than wait to be purged, the Utraquist party in Prague decided on a pre-emptive strike. On September 24, 1483, they executed a coordinated insurrection across the city. Partisans stormed the town halls of the Old and New Towns. At the Old Town Hall, they defenestrated the burgomaster and threw the bodies of other slain councillors out of the windows. The violence forcefully asserted Hussite power and stopped the Catholic plot in its tracks.

The Second Defenestration, though bloody, ultimately led to a resolution. It forced the king to the negotiating table and resulted in the Peace of Kutná Hora in 1485. This landmark agreement formally recognized both Utraquism and Catholicism as equal faiths in Bohemia, establishing a period of religious tolerance that would last for over a century—until the next defenestration shattered it.

The Fall That Ignited a Continent: The Defenestration of 1618

This is the big one—the event that plunged Europe into one of the longest and most destructive wars in its history. By the early 17th century, the religious peace was crumbling. The zealous Habsburg dynasty, rulers of the Holy Roman Empire, was determined to re-establish Catholicism as the sole faith across their domains.

In 1609, the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II had granted Bohemian Protestants religious freedoms in a decree known as the “Letter of Majesty.” But his successor, Ferdinand II, was a fervent Catholic with no intention of honoring this agreement. He began violating its terms, ordering the destruction of Protestant chapels and installing hardline Catholics in positions of power.

On May 23, 1618, a group of irate Protestant nobles marched to Prague Castle to confront two of the Emperor’s top representatives, the imperial regents Jaroslav Bořita of Martinice and Vilém Slavata of Chlum, along with their secretary, Philip Fabricius. After a furious argument in a chamber of the Bohemian Chancellery, the nobles declared the regents enemies of the state for violating the Letter of Majesty. Then, in a chilling echo of 1419, they seized the three men and threw them from a third-story window, some 70 feet (21 meters) to the ground below.

Incredibly, all three survived. This is where the story splits into two powerful propaganda narratives:

- The Catholic Version: The men were miraculously saved by the intervention of angels and the Virgin Mary, who caught them and gently lowered them to the ground. This proved God was on the side of the Emperor and the Catholic faith.

- The Protestant Version: The men landed in a giant, soft pile of horse manure and wet garbage that had accumulated in the castle moat, cushioning their fall. This proved God had a sense of humor, humiliating His enemies by saving them with filth. (The secretary, Fabricius, was later granted the noble title “von Hohenfall”, meaning “of Highfall.”)

Regardless of how they survived, the act itself was an undeniable declaration of war. It was a direct, violent, and humiliating rejection of Emperor Ferdinand II’s authority. This act of rebellion triggered the Bohemian Revolt, which quickly spiraled into the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648). This catastrophic conflict rearranged the map of Europe, confirmed the decline of Spain, led to the rise of France, and killed an estimated 8 million people through combat, famine, and disease.

Why Windows? The Legacy of Defenestration

The Defenestrations of Prague were more than just eccentric acts of violence. They were powerfully symbolic. To be thrown from a high window of a government building was a public and degrading rejection of one’s authority. It was a physical “casting down” from a seat of power, performed in full view of the public.

From the Hussite Wars to the Thirty Years’ War, these dramatic events served as the flashpoints where long-simmering religious and political tensions finally exploded into open conflict. They demonstrate how a single, visceral act of defiance can become the catalyst that sets a nation—and even an entire continent—on a new and often bloody course. In the history of Bohemia, revolution didn’t just knock on the door; it came crashing through the window.