Imagine a world where, as a woman, your future was largely predetermined. Your path was one of two well-trodden roads: marriage, where you would become part of your husband’s household, or the convent, where you would dedicate your life to God behind cloistered walls. For centuries, these were the primary options available. But in the High Middle Ages, a revolutionary third way emerged, one carved out by women, for women. They were the Beguines, and they built communities that were unprecedented in their independence and spirit.

Who Were the Beguines?

The Beguine movement began to flourish in the late 12th and early 13th centuries, primarily in the Low Countries (modern Belgium and the Netherlands) and spreading into northern France and Germany. A Beguine was a laywoman who chose to live a life of religious devotion and service in the world without taking the formal, lifelong vows of a nun. This distinction is crucial.

Unlike nuns, Beguines did not take a vow of perpetual poverty; they could retain their own property and inheritances. They did not take a vow of enclosure; they could leave the community to visit family or, if they chose, leave permanently to get married. Their primary commitment was a promise of chastity and obedience to the community’s rules for as long as they chose to live as a Beguine. This flexibility offered a unique blend of spiritual dedication and personal freedom that was unheard of for women of the era.

A City Within a City: Life in the Beguinage

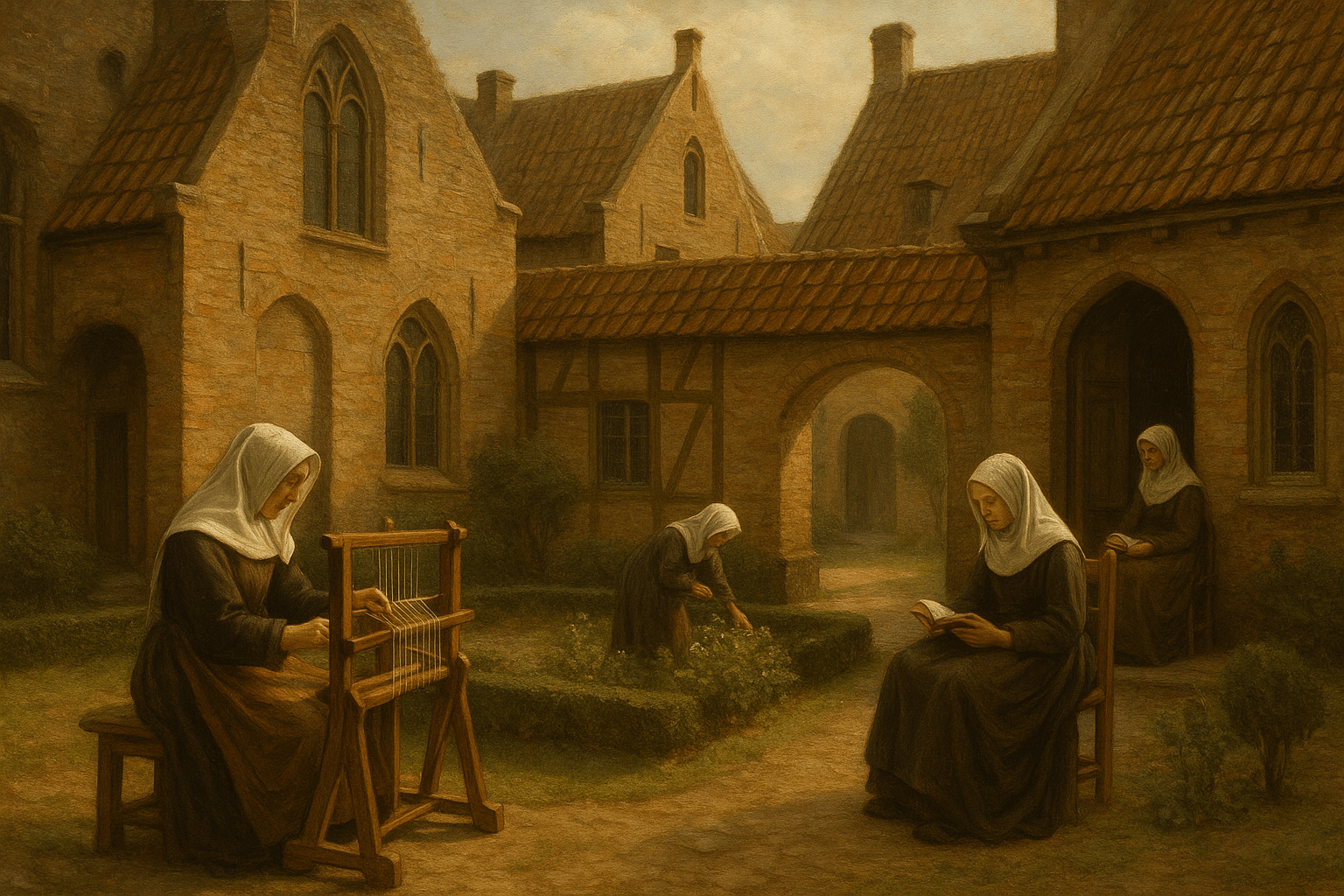

These women didn’t live in isolation. They formed structured, self-governing communities called beguinages (or begijnhof in Flemish). These were often architectural marvels—walled enclosures inside a larger town that functioned as a safe and supportive “city within a city.”

A typical beguinage would include:

- Individual houses for more affluent Beguines or small groups.

- A convent-style building for poorer women or newcomers.

- A central church or chapel for communal worship.

- An infirmary to care for the sick within the community and the wider town.

- Communal spaces for work, such as weaving rooms.

Life was a balanced rhythm of prayer, contemplation, and labor. The Beguines were not idle mystics; they were industrious and economically savvy. Many communities became major players in the booming textile industry, renowned for their skill in weaving, spinning, and lacemaking. Others ran schools for girls, worked as nurses, or prepared the dead for burial. This work was not just for subsistence; it granted them a remarkable degree of economic independence from male control, allowing them to fund their own charitable works and maintain their properties.

Spirituality Without a Cloister

The Beguines were at the forefront of a new, intensely personal form of spirituality. Living in the world, they sought to find God not by retreating from it, but by engaging with it through service and inner contemplation. Theirs was a faith centered on the love of Christ and the pursuit of a direct, mystical union with the divine.

This environment fostered a flowering of female intellectual and literary culture. Because they were not part of the Latin-bound clerical establishment, many Beguines wrote in the vernacular—Middle Dutch, Middle High German, or Old French. This made their profound mystical writings accessible to a lay audience. Figures like Hadewijch of Antwerp wrote searingly passionate poetry about her love for God, while Mechthild of Magdeburg chronicled her divine visions in her seminal work, The Flowing Light of the Godhead. These women were not just practitioners of faith; they were theologians and authors in their own right, shaping religious discourse outside of the university and monastery.

Independence and Suspicion

A community of pious, economically independent, and intellectually vibrant women living without direct male oversight was bound to attract suspicion. The male-dominated Church hierarchy was deeply uncomfortable with the Beguines. They fit into no established category: they were not nuns, but they were not ordinary wives. They governed themselves, electing a “Grand Mistress” to lead their beguinage, and managed their own finances and spiritual lives.

This autonomy was seen as a threat. Accusations began to fly. Critics claimed the Beguines were undisciplined, that their lack of permanent vows encouraged moral laxity, and—most dangerously—that their mystical teachings veered into heresy. An independent woman claiming a direct line to God was a direct challenge to the authority of the priesthood.

The danger became terrifyingly real for Marguerite Porete, a French Beguine. Her book, The Mirror of Simple Souls, described the soul’s annihilation in God to a degree that church authorities deemed heretical. For refusing to renounce her work, she was tried by the Inquisition and burned at the stake in Paris in 1310. Her execution sent a shockwave through the movement. Shortly after, the Council of Vienne (1311–1312) officially condemned the Beguine way of life, accusing them of spreading heresy. While the decree wasn’t universally enforced, it marked the beginning of the end for the Beguines in their freest form.

The Enduring Legacy

In the wake of persecution, many beguinages were forced to disband or place themselves under the authority of a recognized religious order, effectively becoming a type of convent. The movement waned, and by the modern era, only a handful of Beguines remained. The last woman to live the traditional Beguine life, Marcella Pattyn, passed away in 2013.

But their legacy is far from gone. The Beguines were pioneers of social welfare, creating some of the first organized nursing and teaching services for urban communities. They demonstrated that women could form powerful, supportive, and economically self-sufficient communities. And their beautiful, haunting beguinages remain. Today, several Flemish beguinages, such as the grand ones in Ghent, Bruges, and Leuven, are recognized as UNESCO World Heritage sites, serene and poignant reminders of the women who dared to build a world of their own.

The story of the Beguines is more than a historical footnote. It is a powerful testament to female resilience, innovation, and the enduring quest for a life of purpose and freedom, on one’s own terms.