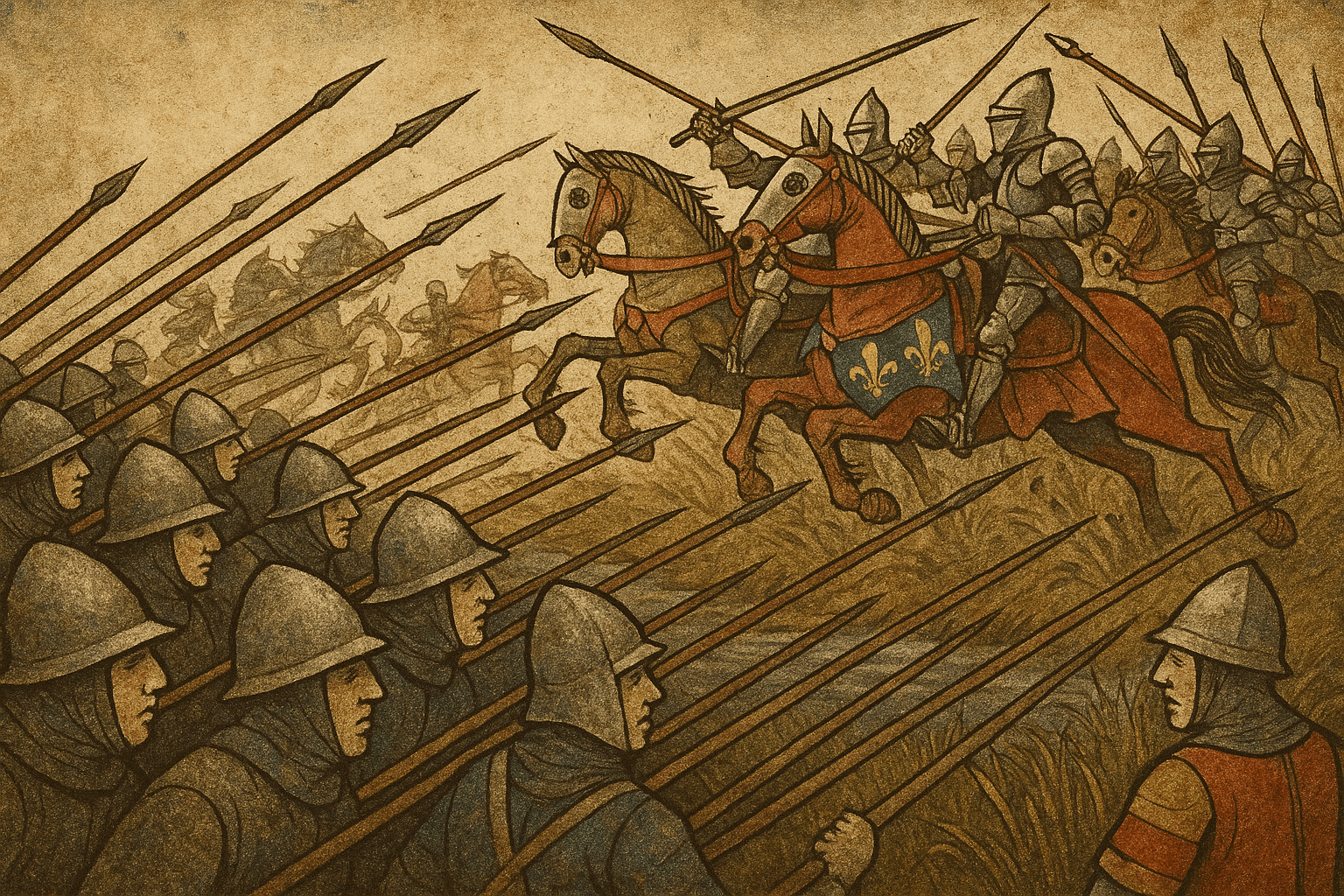

Imagine the quintessential medieval warrior: a nobleman encased in steel, mounted on a powerful warhorse, lance couched and ready to charge. For centuries, the heavy cavalry knight was the undisputed king of the battlefield—a living, breathing tank that could shatter infantry lines with a single, thunderous assault. Then came July 11, 1302. On a marshy field outside the Flemish city of Kortrijk, this entire military doctrine was brought to a bloody, muddy, and shocking halt.

On that day, an army composed not of nobles, but of weavers, butchers, and artisans from the cities of Flanders, accomplished the unthinkable. They stood their ground against the flower of French chivalry and utterly destroyed them. This is the story of the Battle of the Golden Spurs, a stunning upset that sent shockwaves across Europe and forever changed the art of war.

The Seeds of Rebellion: Flanders vs. France

To understand the battle, one must first understand the unique position of the County of Flanders (in modern-day Belgium). While technically a vassal state of the French crown, Flanders was an economic powerhouse. Its bustling cities—Bruges, Ghent, and Ypres—were the heart of Europe’s cloth trade, transforming English wool into highly sought-after textiles. This immense wealth gave the Flemish cities a fierce spirit of independence.

This independence did not sit well with the ambitious French king, Philip IV, known as “Philip the Fair.” Seeking to centralize his power and, more importantly, tax the rich Flemish cities to fund his wars, Philip began to assert his authority. He found allies among the wealthy patricians in the cities, a pro-French faction known as the Leliaards (the “Lily-men”, for the French fleur-de-lis). They were opposed by the common people and guild members, who championed Flemish independence. This faction was known as the Klauwaerts (the “Claw-men”, referring to the claws of the Flemish Lion).

In 1300, Philip IV marched into Flanders, deposed the ruling Count, and appointed his own governor, Jacques de Châtillon. Heavy taxes and the oppressive presence of French garrisons soon pushed the common folk to their breaking point.

The Bruges Matins: A Point of No Return

The spark that ignited the full-scale rebellion came in the pre-dawn hours of May 18, 1302, in the city of Bruges. In an event known as the Bruges Matins, a small group of rebels, led by the weaver Pieter de Coninck and the butcher Jan Breydel, launched a surprise attack on the French garrison stationed in the city.

To identify friend from foe in the dark, the Flemings used a shibboleth—a phrase the French would find nearly impossible to pronounce correctly: “Schild en Vriend” (“Shield and Friend”). Any who stumbled over the guttural Flemish sounds were cut down. Hundreds of French soldiers and their Leliaard supporters were slaughtered. The message was clear: compromise was over. The cities of Flanders were in open revolt.

The Armies Assemble: David vs. Goliath

King Philip was enraged. He assembled a formidable professional army to crush the rebellion once and for all. Led by one of France’s most experienced commanders, Count Robert II of Artois, the army was a spectacle of medieval military might. Its core consisted of over 2,500 heavily armored noble knights, supported by thousands of professional infantry, including crossbowmen and spearmen.

Their opponents were a motley crew by comparison. The Flemish army was a citizen militia, not a professional force. It was made up of thousands of members from the urban guilds, commanded by William of Jülich and Guy of Namur (grandsons of the deposed Flemish Count). They had almost no cavalry and few archers. Their primary weapons were the long pike and a uniquely Flemish innovation: the goedendag (“good day”).

The goedendag was a brutally effective weapon. It was a thick wooden staff, about five feet long, that tapered at the end and was topped with a sharp steel spike. It could be used as a club to knock a knight from his horse and as a short spear to pierce armor in close quarters. It was the perfect tool for an infantryman facing a mounted knight.

The Muddy Fields of Kortrijk

The Flemings knew they couldn’t beat the French in a straight fight on an open field. Their only chance was to choose the terrain and force the French to fight on their terms. They took up a defensive position in front of the city of Kortrijk, strategically positioning themselves behind a series of marshy streams and ditches, most notably the Groeningebeek.

They formed a deep, solid line—a hedgehog of pikes and goedendags pointing outward. Their plan wasn’t to attack, but to receive the legendary French cavalry charge and break it. The knights, they gambled, would be so eager for glory that they would overlook the treacherous, waterlogged ground hidden beneath the summer grass.

The Charge and the Carnage

On July 11, the French army arrived. The battle began with an exchange between the French infantry and the Flemish front line. The French crossbowmen were effective, but just as they were gaining an advantage, Robert of Artois made a fatal, arrogant decision. Fearing the common infantry would steal the glory of victory, he ordered them to pull back to clear the way for his knights.

The French trumpets sounded the charge. With a thunder of hooves, the elite knights of France galloped across the field, lances lowered, expecting to smash through the peasant rabble. Instead, they plunged directly into the hidden streams and muddy ditches. The powerful, disciplined charge devolved into a chaotic, floundering mess. Horses stumbled and fell, throwing their heavily armored riders into the mud, where they were unable to get up.

This was the moment the Flemings had waited for. Maintaining their disciplined formation, they advanced on the immobilized knights. The Flemish militia swarmed the bogged-down cavalry, using their goedendags with brutal efficiency. They pulled knights from their horses and systematically dispatched them on the ground. The battle turned into a one-sided slaughter. Robert of Artois himself led a desperate second charge, managed to cross the stream, but was quickly surrounded, unhorsed, and killed.

With their leader dead and their elite cavalry shattered, the rest of the French army broke and fled.

The Legacy of a Thousand Spurs

The Flemish victory was total. In the aftermath, the victors combed the battlefield, collecting the prized golden spurs from the heels of the slain French nobles—the ultimate symbol of knighthood. Between 500 and 1,000 pairs of these spurs were gathered and hung in triumph from the rafters of the Church of Our Lady in Kortrijk, giving the battle its famous name.

The Battle of the Golden Spurs was a seismic event. It secured Flemish independence for nearly two decades and dealt a humiliating blow to the French monarchy. But its true significance was military. It was one of the first major medieval battles to prove that a well-equipped, disciplined infantry force could defeat an army of elite heavy cavalry by using terrain and tactical patience. It was a lesson that would be reinforced later in the Hundred Years’ War at Crécy and Agincourt, signaling the dawn of the “infantry revolution” and the slow decline of the mounted knight’s supremacy.

The battle remains a cornerstone of Belgian and Flemish identity—a powerful symbol of a people’s victory against a foreign oppressor. It was a bloody lesson, written in the mud of Kortrijk, that the strength of an army lies not just in the status of its warriors, but in their discipline, strategy, and the will to fight for their freedom.