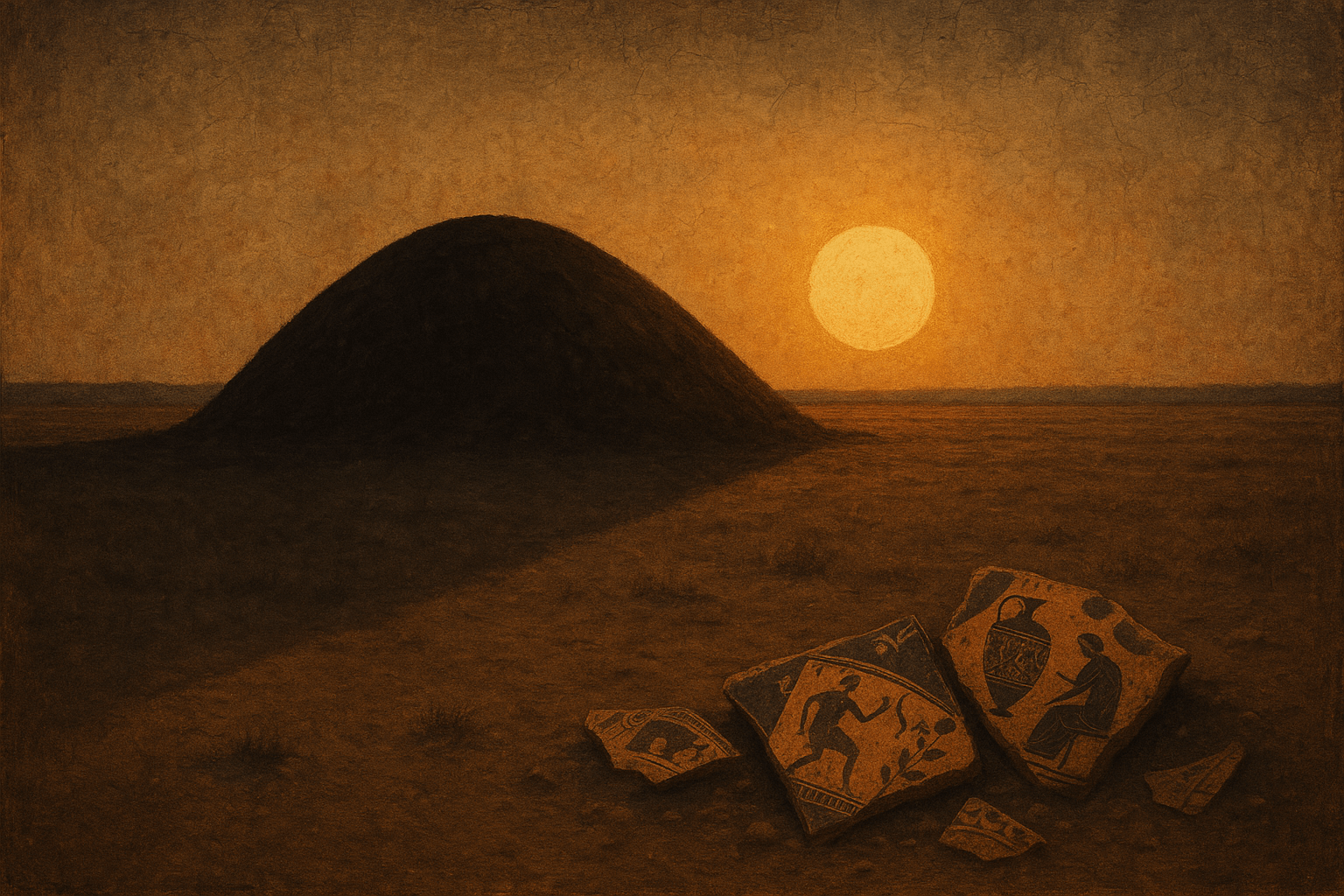

The story is etched into our collective memory: a lone runner, Pheidippides, sprinting 26 miles from the battlefield of Marathon to Athens, crying out “Νενικήκαμεν!” (“We have won!”) with his final breath. It’s a tale of heroic endurance that inspired the modern marathon race. But while the run has become a global phenomenon, the profound story left behind on the battlefield is often overlooked. It’s a story sealed beneath a simple, grass-covered mound of earth—the Soros, the final resting place of the 192 Athenian soldiers who died securing that legendary victory.

This is not just a grave; it is one of the most significant monuments in Western history. The Soros is the physical embodiment of a pivotal moment, and for centuries, it served as the heart of Athenian identity, a sacred touchstone for the world’s first democracy.

A Victory Etched in Blood and Soil

In 490 BCE, the democratic experiment of Athens faced an existential threat. The mighty Persian Empire, under King Darius I, landed a massive expeditionary force on the shores of Marathon, aiming to crush the city-state and extinguish its radical ideas of citizen rule. Against a Persian army that may have outnumbered them by more than two to one, the Athenian hoplites, along with their loyal allies from the city of Plataea, prepared for a desperate defense.

Under the brilliant and audacious command of the general Miltiades, the Athenians deployed a radical strategy. They deliberately thinned their center and heavily reinforced their flanks. As the battle commenced, the weaker Athenian middle buckled and fell back, luring the elite Persian infantry and cavalry inland. It was a trap. The powerful Athenian wings then wheeled inward, enveloping the surprised Persian force and routing them in a stunning display of tactical genius. The Persians fled back to their ships, leaving over 6,000 dead on the field. The Athenian cost was miraculously light, but deeply felt: 192 citizen-soldiers fell.

An Unprecedented Honor: Burying Heroes on the Battlefield

In ancient Athens, tradition dictated a specific and solemn ritual for the war dead. The fallen were to be brought back to the city, their bones interred in the public cemetery, the Kerameikos, following a state funeral and a eulogy delivered by a prominent statesman. But for the men who fell at Marathon, Athens broke with centuries of tradition.

In a decision of immense symbolic weight, the city chose to cremate and bury the 192 heroes together on the very ground where they had died. This act transformed the battlefield from a site of conflict into a sacred precinct (temenos). By burying them there, the Athenians declared that the sacrifice of these men was so extraordinary, so fundamental to the city’s survival, that they must forever guard the land they saved. The great earthen mound, or tumulus, known as the Soros (meaning “heap” or “mound”), was raised over their ashes. It was not just a tomb; it was an eternal monument to civic virtue and democratic defiance.

The Mound that Shaped Athenian Identity

In the decades that followed, the victory at Marathon became the foundational myth of Athens’s Golden Age. The “Men of Marathon”, the Marathonomachoi, were revered as the ideal citizens, paragons of courage who had sacrificed everything for freedom. Orators like Pericles would evoke their memory to inspire future generations. To be compared to a Man of Marathon was the highest honor.

The Soros was the physical anchor for this powerful cultural memory. It became a site of pilgrimage and reverence. For nearly 600 years after the battle, the writer and traveler Pausanias visited the site and described it in his Description of Greece. He noted the Soros, as well as a separate tomb for the fallen Plataeans. He even recounted local legends that on the anniversary of the battle, one could still hear the ghostly sounds of whinnying horses and clashing men on the plain. The mound kept the story alive, embedding the heroic narrative of Marathon into the very landscape of Greece.

For Athenians, the Soros was proof that their democracy was not just an abstract idea but something worth dying for—a principle defended by ordinary citizens who rose to an extraordinary challenge.

From Myth to Matter: Unearthing the Soros

For centuries, the Soros was known only through ancient texts like those of Herodotus and Pausanias. A prominent mound stood on the Marathon plain, but was it truly the legendary tomb of the 192 Athenians? The answer came in 1890, when the Greek archaeologist Valerios Stais began a systematic excavation.

As his team dug into the heart of the 30-foot-high mound, they uncovered a thick layer of ash, charcoal, and cremated human bones—the clear remnants of a massive funeral pyre. Scattered among the remains were funerary offerings that provided the crucial, definitive evidence. Stais’s team found dozens of vases, particularly black-figure lekythoi (oil flasks), which archaeologists could stylistically date to the period immediately around 490 BCE. The pottery was exactly what would be expected for a burial from the time of the Persian Wars.

The excavation confirmed the literary tradition with archaeological fact. The Soros was real. The men who saved Athens were indeed buried right there.

A Silent Witness to History

Today, the Soros stands as a quiet, powerful sentinel on the Marathon plain. Stripped of any elaborate decoration, the simple, grass-covered hill possesses a profound dignity. It is surrounded by a small park, a place for quiet contemplation far removed from the bustling energy of modern Athens.

To stand before it is to connect with a moment that shaped the course of history. It reminds us that the celebrated marathon run was born from a brutal, desperate battle and an incredible victory. More importantly, the Soros reminds us of the cost. It is a monument not to a single hero, but to a collective—192 citizens who stood together, fell together, and were honored together. In its silent, earthen form, the Soros tells a more enduring story than any legend of a single runner: that of the birth of democratic resilience, paid for in blood and immortalized in soil.