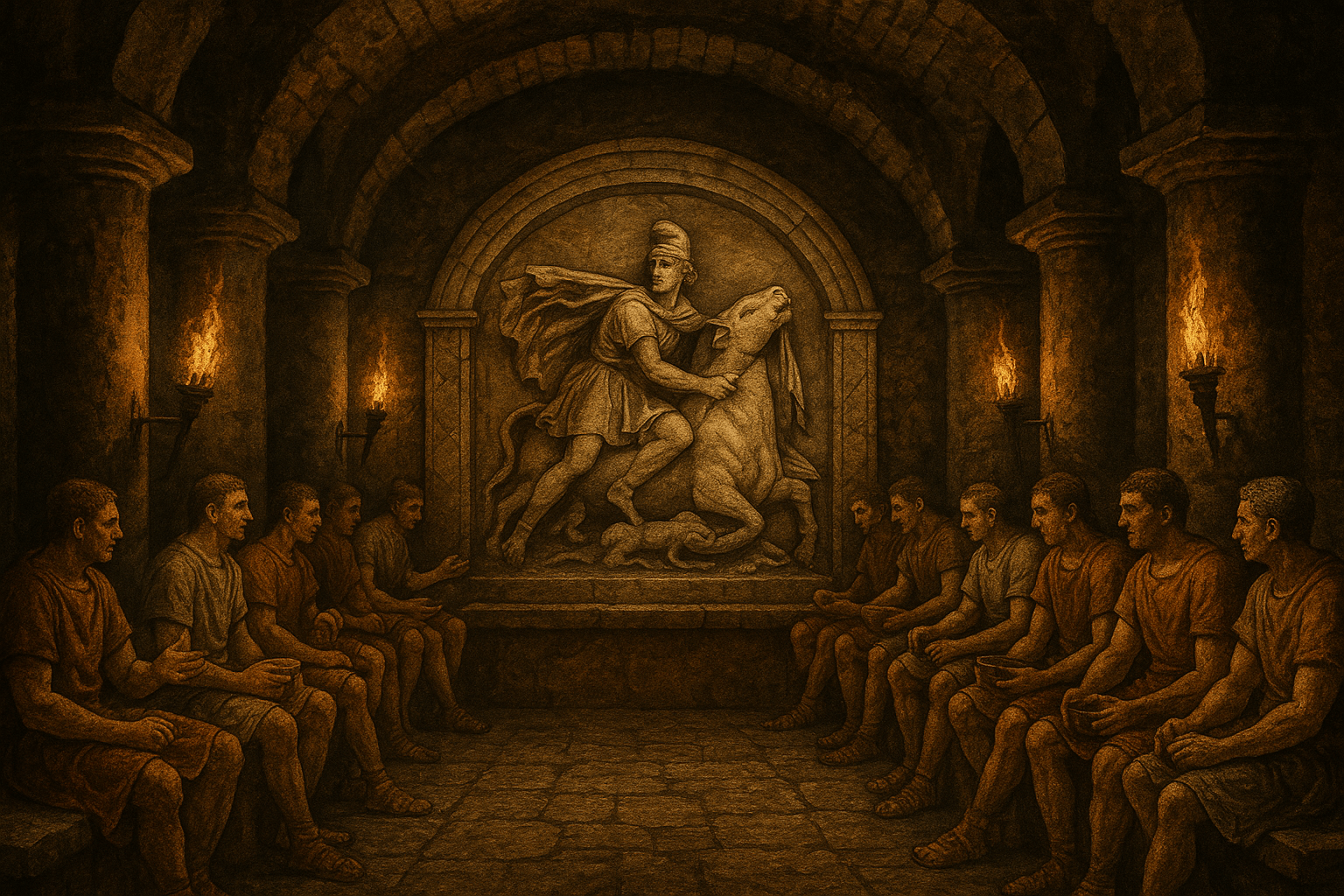

Imagine yourself a Roman legionary stationed on the misty frontier of Britannia or along the sun-baked borders of Syria in the 2nd century AD. Your life is one of discipline, danger, and duty to the Emperor. But in the quiet hours, away from the barracks, you belong to a different kind of army—a secret spiritual brotherhood. You descend a narrow flight of stairs into a dark, cave-like chamber, the air thick with incense. At the far end, illuminated by flickering torchlight, is a dramatic carving: a youthful god in a strange, peaked cap, plunging a dagger into the neck of a powerful bull. This was the world of Mithraism, one of the Roman Empire’s most enigmatic and popular mystery cults.

Who Was Mithras? From Persia to Rome

While the name “Mithras” has its roots in the ancient Persian god Mithra—a deity of contracts, light, and heavenly order—the Roman version was a distinctly different and new creation. The Mithra worshiped by Roman soldiers was not simply a transplant from the East. Instead, he was the central figure of a new Roman “mystery religion” that emerged in the late 1st century AD. These religions offered personal salvation, a direct connection with the divine, and a sense of belonging that the formal, transactional state religion of Rome often lacked.

Unlike the public ceremonies for Jupiter or Mars, the rites of Mithras were for initiates only. The cult was particularly popular among soldiers, merchants, and imperial administrators—men whose lives involved travel, loyalty, and a shared hierarchical structure. It spread rapidly through the arteries of the Empire, with temples (called Mithraea) found from the Hadrian’s Wall in England to the desert city of Dura-Europos in modern-day Syria.

The Mithraeum: A Temple Beneath the Streets

A follower of Mithras didn’t worship in a grand, sunlit temple in the city forum. Instead, they gathered in a Mithraeum. These spaces were designed to be intimate and secretive, often built underground or within existing buildings to be windowless, simulating the primordial cave where Mithras performed his great sacrifice. A typical Mithraeum was a long, narrow chamber with raised stone benches running along the sides where the faithful would recline for sacred meals. They were small, rarely holding more than 30 men at a time, reinforcing the cult’s exclusivity and the tight-knit bond between its members.

Archaeologists have uncovered hundreds of these sites across the former empire. One of the most famous is located deep beneath the Basilica of San Clemente in Rome. Visiting it today, you can descend through layers of history—from the 12th-century church, down to a 4th-century church, and finally into the 1st-century Roman building that houses the Mithraeum, complete with its stone benches and the central altar still in place. It’s a powerful physical reminder of how this “underground” cult was literally buried by the rising tide of a new faith.

The Central Mystery: Mithras and the Bull

At the heart of every Mithraeum was the Tauroctony, a relief or statue depicting the cult’s central, defining act: Mithras slaying a bull. This was not a simple image of a hunt; it was a complex cosmological drama packed with symbolism.

Let’s break down the iconic scene:

- Mithras: He is depicted as a vigorous young man, wearing a Roman tunic and a distinctive Phrygian cap (a soft, conical hat associated with peoples from the East). He is strong yet graceful, and crucially, he often looks away from the bull, as if the act is a solemn duty rather than one of passion.

- The Bull: The powerful, sacrificial victim.

- The Animals: A dog and a snake are typically shown lapping at the blood pouring from the bull’s wound. A scorpion attacks the bull’s genitals. A raven sits near Mithras, perhaps acting as a messenger from the sun god, Sol. Sometimes, stalks of wheat are shown sprouting from the bull’s tail.

Scholars believe the Tauroctony is not a myth in the traditional sense, but an astrological allegory. The act of slaying the bull is a creative sacrifice. From the death of this one primordial creature, all life on Earth springs forth. The bull’s blood fertilizes the ground (represented by the snake and dog), and its semen, attacked by the scorpion, is purified and gives rise to all useful animals. The wheat from its tail represents the origin of agriculture. It is an act of cosmic re-ordering, guided by Mithras, that establishes the cycles of life and death and guarantees salvation for his followers.

The Path of Initiation: Climbing the Seven Grades

Mithraism was an exclusively male cult structured around seven hierarchical grades of initiation. Each initiate had to progress through the ranks, likely undergoing tests, swearing oaths, and learning secret knowledge at each stage. The seven grades, each associated with a celestial body and a specific mask or costume for rituals, were:

- Corax (Raven): Servant, associated with Mercury.

- Nymphus (Bridegroom): Associated with Venus.

- Miles (Soldier): A spiritual warrior, linked to Mars. Initiates may have undergone a branding ritual or taken a sacred oath (sacramentum) like a real soldier.

- Leo (Lion): Associated with Jupiter. These members handled fire in rituals.

- Perses (Persian): A nod to the cult’s origins, linked to the Moon.

- Heliodromus (Sun-Runner): The emissary of the Sun, associated with Sol.

- Pater (Father): The highest rank, the leader of the congregation, associated with Saturn.

This ladder of initiation provided a clear path for advancement and personal achievement, mirroring the military and administrative careers of many of its members. It created a powerful sense of community and shared purpose among men far from home.

The Vanishing Act: Why Did Mithraism Disappear?

For nearly three centuries, Mithraism thrived. So why did it vanish so completely? While no single reason accounts for its demise, several factors contributed to its disappearance by the early 5th century.

Firstly, its greatest strengths were also its weaknesses. The cult’s secrecy and all-male exclusivity meant it could never become a mass religion. It excluded women, children, and families, limiting its demographic reach compared to faiths like Christianity, which welcomed all.

Secondly, Mithraism had no central authority or foundational text like the Bible. Each Mithraeum was largely autonomous. This made it vulnerable to disruption. When a legion was transferred, its local Mithraic community often dissolved.

The decisive blow, however, came from the rise of institutional Christianity. As Christianity gained imperial favor in the 4th century, it moved from a persecuted sect to the state-sanctioned religion. Pagan cults were suppressed. In 391 AD, Emperor Theodosius I outlawed pagan sacrifices. Mithraea were abandoned, deliberately destroyed, or consecrated as Christian sites. Because its doctrines were transmitted orally and never written down, once the last Pater died and the last Mithraeum was sealed, the secrets of Mithras were lost to history.

Today, all we have are the silent, stone witnesses in their underground caves. They hint at a vibrant and complex spiritual world that once offered comfort and purpose to the men who built and guarded the Roman Empire, a faith that ultimately succumbed to the changing tides of history, leaving only a captivating mystery in its wake.