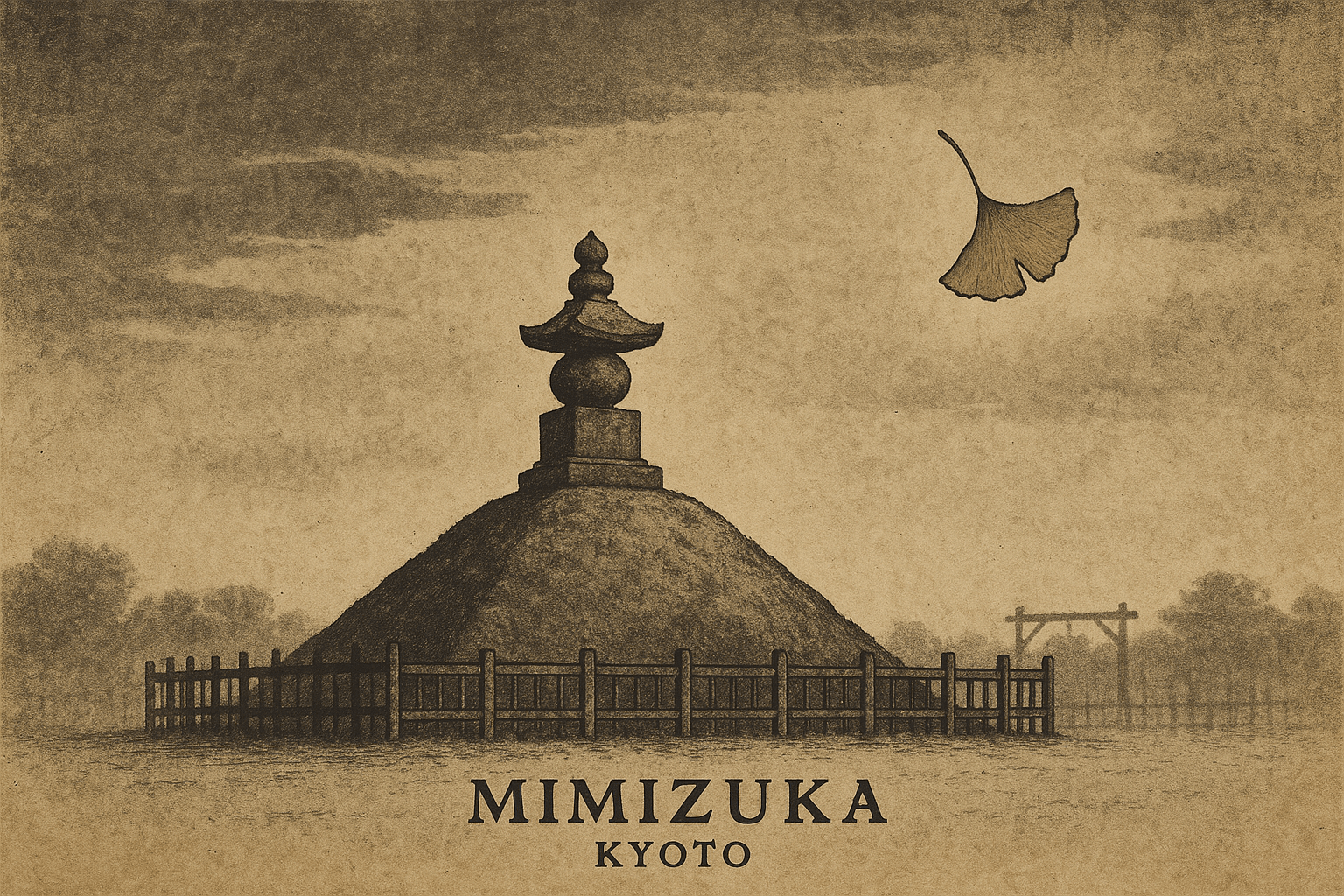

Kyoto, the former imperial capital of Japan, is a city synonymous with grace and beauty. It’s a landscape of serene Zen gardens, vermilion Shinto shrines, and graceful geishas gliding through lantern-lit alleys. But nestled just west of the Toyokuni Shrine, a monument dedicated to one of Japan’s great unifiers, lies a site that starkly contrasts this tranquil image. It is an unassuming grassy knoll, about 10 meters high, crowned with a stone pagoda. This is the Mimizuka (耳塚), or “Ear Mound”, a name that does little to soften the horrifying truth of what lies beneath: the pickled noses and ears of at least 38,000 Korean and Chinese soldiers and civilians.

This grim burial mound is a direct and visceral link to one of the most brutal conflicts in East Asian history. It is a monument not of honor, but of slaughter; a war trophy’s legacy that continues to cast a long, dark shadow over modern relations between Japan and Korea.

The Bloody Ambition of the Imjin War

To understand the Mimizuka, we must travel back to the late 16th century. Japan, after a century of civil war, had finally been unified under the formidable warlord Toyotomi Hideyoshi. With domestic peace secured, Hideyoshi turned his ambitions outward. His ultimate goal was the conquest of Ming Dynasty China, and the Korean Peninsula was the necessary stepping stone. In 1592, and again in 1597, Hideyoshi launched two massive invasions of Korea, unleashing a force of over 150,000 battle-hardened samurai and soldiers. These invasions are known collectively as the Imjin War (or in Korea, the Imjin Waeran).

The conflict was devastating. Japanese forces, employing firearms (arquebuses) they had acquired from the Portuguese, initially swept through the peninsula. Cities were sacked, farmlands burned, and countless people were massacred or enslaved. While the Korean navy, under the brilliant leadership of Admiral Yi Sun-sin, won stunning victories at sea, the battles on land were a grinding, brutal affair. It was within this context of total war that the gruesome practice of collecting war trophies began on an industrial scale.

A Gruesome Accounting: From Heads to Noses

In samurai warfare, taking the head of a defeated enemy was a long-standing tradition. A warrior’s rank and reward were often determined by the number and status of the heads he presented to his commander. It was a martial proof of valor. However, the sheer distance and scale of the Korean campaigns presented a logistical problem. Shipping tens of thousands of heads back to Japan from the Korean mainland was impractical.

Hideyoshi’s commanders devised a brutally efficient solution. Instead of whole heads, samurai were ordered to take a more portable proof of a kill: the nose. Severed noses (and often ears as well) could be sliced off quickly, preserved in salt or rice wine, packed into barrels, and shipped to Japan for an official count. This created a ghastly incentive system. A samurai’s pay and prestige were tied directly to the number of noses he collected.

The system inevitably led to indiscriminate slaughter. When enemy soldiers were scarce, samurai turned on the civilian population. Men, women, and even children were hunted down and mutilated to fill the quotas. Accounts from the era, including Korean records and even the diaries of some Japanese participants, describe horrific scenes of entire villages being wiped out. The noses were a currency of death, and the business of war was booming.

From Trophies to a Tomb: The Creation of the Mimizuka

The barrels of human remains arrived in Japan and were tallied. To commemorate his “victorious” campaign, Toyotomi Hideyoshi ordered the creation of a burial mound in 1597. It was strategically placed in Kyoto, near the Hokoku-jinja, a shrine he was constructing to have himself deified as a god of prosperity and fortune. The noses were interred, and a monument was built.

Originally, the mound was called Hanazuka (鼻塚), literally “Nose Mound.” The name was direct and unapologetic—a monument to military might, a terrifying testament to the subjugation of Hideyoshi’s enemies. It was a symbol of power, not of penance.

However, over the following decades, a linguistic shift occurred. Perhaps guided by Buddhist scholars or a sense of decorum to soften the monument’s blatant cruelty, the more euphemistic name Mimizuka (耳塚), or “Ear Mound”, came into use. While equally gruesome, the name was somehow considered less shocking. Despite its name, historical records confirm the majority of the trophies interred were, in fact, noses.

The mound was consecrated with Buddhist ceremonies, supposedly to give “peace” to the spirits of the slain. This adds another layer of complexity. Was it a genuine, if misguided, act of religious atonement? Or was it a cynical political act, using religious ritual to legitimize a monument built on atrocity? For Hideyoshi, it was likely the latter—a grand gesture that simultaneously displayed his power and gave it a veneer of spiritual gravity.

A Monument of Silence and Contention

Today, the Mimizuka stands in a quiet park, largely unnoticed by the millions of tourists who flock to Kyoto. There are no major signs in English, and it is conspicuously absent from most official guidebooks. Many local Japanese citizens are unaware of its existence or its horrifying history. For decades, it was a piece of difficult history that was easier to ignore than to confront.

For South Koreans, however, the Mimizuka is anything but forgotten. It is a painful and potent symbol of Japanese aggression and historical trauma. It is seen as an unhealed wound, a physical reminder of a brutal invasion that preceded the 20th-century Japanese occupation of Korea. Korean tourist groups and officials often make solemn visits to the site to pay their respects, leaving flowers and burning incense for the souls entombed there.

Over the years, there have been calls from South Korean civic groups and individuals for the remains to be excavated and repatriated to Korea for a proper burial. These calls are met with a complex response in Japan. Some Japanese citizens, ashamed of this dark chapter, actively work to raise awareness about the Mimizuka and hold annual memorial services. Officially, however, the site is designated a cultural property, and there is reluctance to disturb it, with some arguing that the spirits are at peace and should not be moved.

The Mimizuka is therefore trapped between its past and its present. It is a tomb for victims, a trophy for a conqueror, a site of Buddhist repose, and a source of modern diplomatic friction. It is a silent testament to the horrors of war that refuses to be completely silenced. As we seek to understand history, it is sites like the Mimizuka that challenge us to look beyond the celebrated narratives of unifiers and conquerors, and to instead remember the ordinary people whose lives were destroyed in their wake.