A Ship on the Horizon: The Arrival of the “Southern Barbarians”

Our story begins in Japan’s turbulent Sengoku, or “Warring States”, period. In 1543, a Chinese ship with Portuguese traders aboard was blown off course, landing on the small island of Tanegashima. The Japanese were fascinated by these “Nanban” (Southern Barbarians) and, more importantly, by their technology: the arquebus matchlock rifle. This single invention would revolutionize Japanese warfare.

Six years later, in 1549, another ship arrived in Kagoshima, this time carrying the Jesuit missionary Francis Xavier. Riding the coattails of the Portuguese traders, Xavier and his fellow Jesuits came with a different commodity: a new faith. They arrived in a land of immense political fragmentation, where powerful daimyō (feudal lords) vied for supremacy. This chaos proved to be fertile ground. Many daimyō, particularly in the western region of Kyushu, saw a strategic advantage in adopting the foreigners’ religion. Converting, or at least tolerating the missionaries, meant preferential access to the lucrative Nanban trade and its coveted firearms.

The Flourishing Faith: Warlords, Trade, and Devotion

The Jesuit strategy was “top-down.” By converting a powerful lord, they knew that many of his subjects would follow, either by decree or devotion. The first daimyō to be baptized was Ōmura Sumitada in 1563. His conversion was so complete that he gifted the strategic port of Nagasaki to the Jesuits in 1580, transforming the small fishing village into a bustling international hub and the heart of Japanese Christianity.

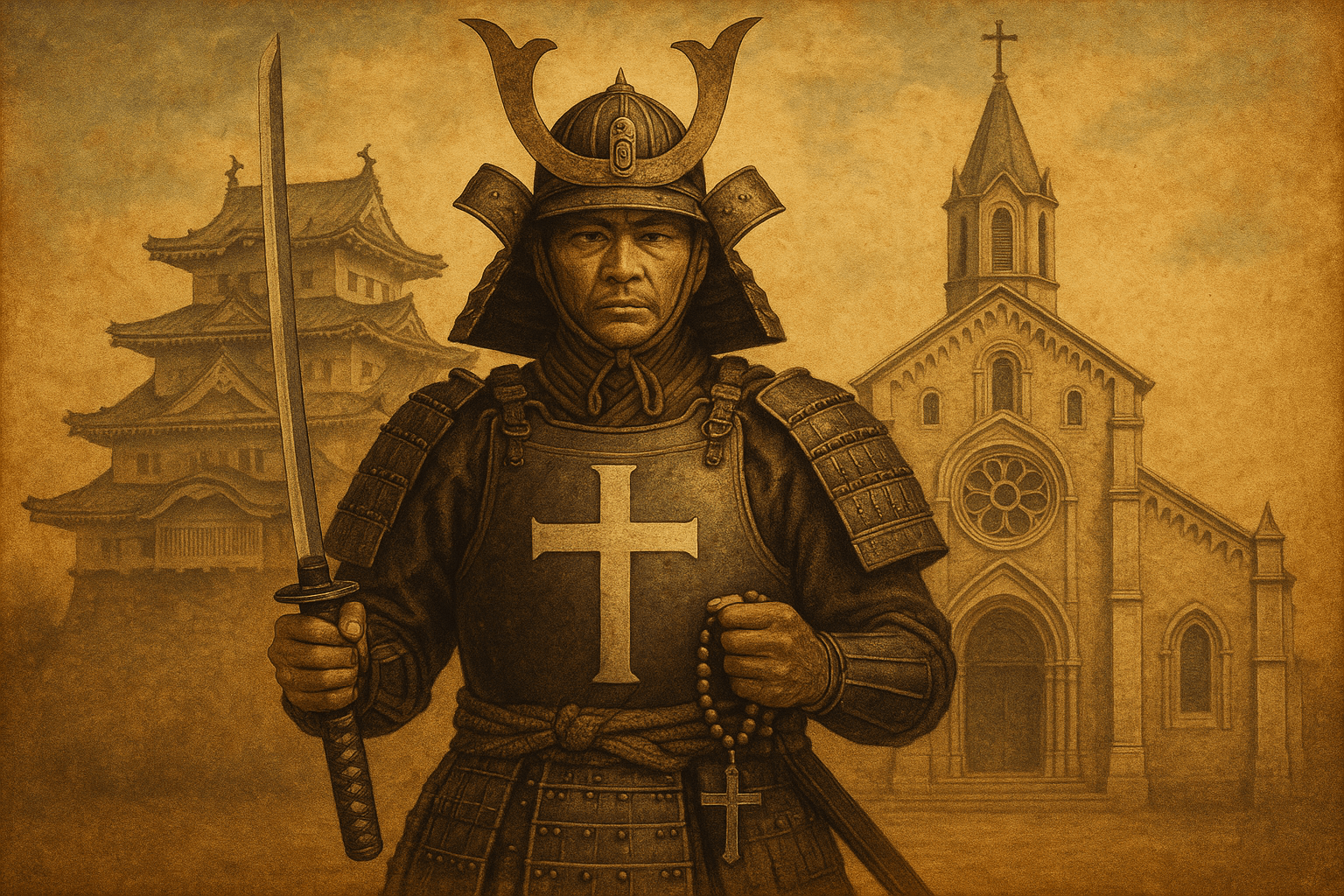

Other powerful figures followed, including the influential Ōtomo Sōrin of Bungo and the devout Takayama Ukon, the “Christian Samurai”, who would later sacrifice his domain for his faith. The missionaries established schools, seminaries, and even a printing press that produced religious texts and dictionaries in Japanese. By the 1580s, the number of Japanese Christians—known as Kirishitan—had swelled to an estimated 300,000, representing a significant portion of the population. For a time, it seemed the Cross might permanently join the Chrysanthemum as a symbol of Japan.

A Collision of Worlds: Kirishitan Art and Culture

This period of exchange produced a unique and beautiful hybrid culture. The most famous examples are found in “Nanban art.” Artists created stunning folding screens depicting the arrival of the great Portuguese “black ships” (kurofune), their decks crowded with foreign merchants and priests in their striking attire. These screens weren’t just decorative; they were windows into a new world, capturing the mutual curiosity and exoticism of the encounter.

Religious art also saw a fascinating fusion. Japanese artisans trained in Western techniques produced paintings and icons, but often with a distinctly local feel. Images of the Virgin Mary sometimes took on the serene, graceful features of a Buddhist Bodhisattva, like Kannon. Exquisite lacquerware, traditionally used for household items, was adapted to create liturgical objects like pyxes and portable altars, decorated with mother-of-pearl crosses and Christian symbols hidden among traditional Japanese motifs.

The Tide Turns: Suspicion and Suppression

The success of the Kirishitan movement, however, carried the seeds of its own destruction. The unifier Toyotomi Hideyoshi, who brought the Sengoku period to an end, grew deeply suspicious. He was troubled by several factors:

- Divided Loyalty: He questioned whether Christian daimyō’s allegiance was to him or to a distant Pope in Rome.

- Destruction of Japanese Culture: He was angered by reports of converts burning Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines at the behest of some missionaries.

- The Threat of Colonization: Hideyoshi became aware of how Spain had used missionaries as a precursor to its conquest of the Philippines and feared Japan could be next.

In 1587, Hideyoshi issued his first edict expelling the missionaries. While not immediately enforced with rigor, it marked a decisive shift. The breaking point came in 1597 when, as a chilling warning, he ordered the crucifixion of 26 Christians—six European Franciscans and twenty Japanese converts—in Nagasaki. They would become known as the Twenty-Six Martyrs of Japan.

The Cross and the Sword: Persecution and Finality

After Hideyoshi’s death, Tokugawa Ieyasu, founder of the Tokugawa Shogunate, initially tolerated Christianity to protect his trade interests. However, his successor, Hidetada, and grandson, Iemitsu, saw the faith as an existential threat to their consolidated power and social order. In 1614, the shogunate issued a nationwide ban on Christianity and began a systematic and brutal campaign of persecution.

To identify hidden believers, officials implemented the fumi-e (“trampling picture”) test. Suspects were forced to step on a bronze or wooden image of Christ or the Virgin Mary. Hesitation meant arrest, torture, and often death. The tortures were horrific, designed to force apostasy, with the most infamous being the “ana-tsurushi” (the pit), where victims were hung upside down over a pit of filth to prolong their suffering.

The final, bloody chapter was the Shimabara Rebellion of 1637-38. While primarily a peasant revolt against crushing taxes, it was led by disenfranchised Christian ronin and peasants who fought under banners bearing Christian slogans. The shogunate mobilized over 125,000 samurai to crush the 37,000 rebels. The rebellion’s brutal suppression was the final nail in the coffin for public Christianity. In 1639, the Tokugawa Shogunate enacted the full sakoku (“closed country”) policy, drastically limiting foreign trade and cutting Japan off from the Western world for over 200 years, largely to ensure a foreign religion could never again threaten its stability.

Echoes of the Kirishitan Century

Though the churches were destroyed and the faith outlawed, it was not extinguished. Thousands of Kirishitan went into hiding, becoming the Kakure Kirishitan (“Hidden Christians”). For 250 years, they practiced their faith in absolute secrecy, disguising statues of Mary as Buddhist Kannon, chanting prayers that sounded like Buddhist sutras, and baptizing their children in secret. When Japan reopened to the world in the mid-19th century, missionaries were stunned to discover tens of thousands of these hidden communities, who had preserved a unique, syncretic version of the faith passed down through generations. The Kirishitan Century stands as a powerful, poignant chapter in world history—a testament to the complex dynamics of cultural encounter and the extraordinary resilience of human belief.