The Venetian Secret: Forging Clarity from Sand

While ancient civilizations like the Egyptians and Romans were masters of glass-making, their creations were typically colorful, opaque, and used for decorative items like beads and vessels. The idea of perfectly transparent glass—a window you could actually see through without distortion—remained elusive. This all changed in the late 13th and early 14th centuries in the Republic of Venice.

Fearing the devastating fires that their furnaces could cause in the crowded city, the Venetian government relocated all glass production to the nearby island of Murano in 1291. Isolated and under the watchful eye of the state, Venetian artisans perfected a new kind of glass. By using quartz pebbles and purifying soda ash, they created cristallo, a substance so clear and brilliant it resembled natural rock crystal. The Venetians guarded their techniques with ruthless jealousy; any glassmaker who attempted to share the secrets abroad faced imprisonment or even assassination. Why such intensity? Because they understood they hadn’t just created a new luxury good—they held the key to a new way of seeing.

A Second Sight: Extending the Mind’s Prime

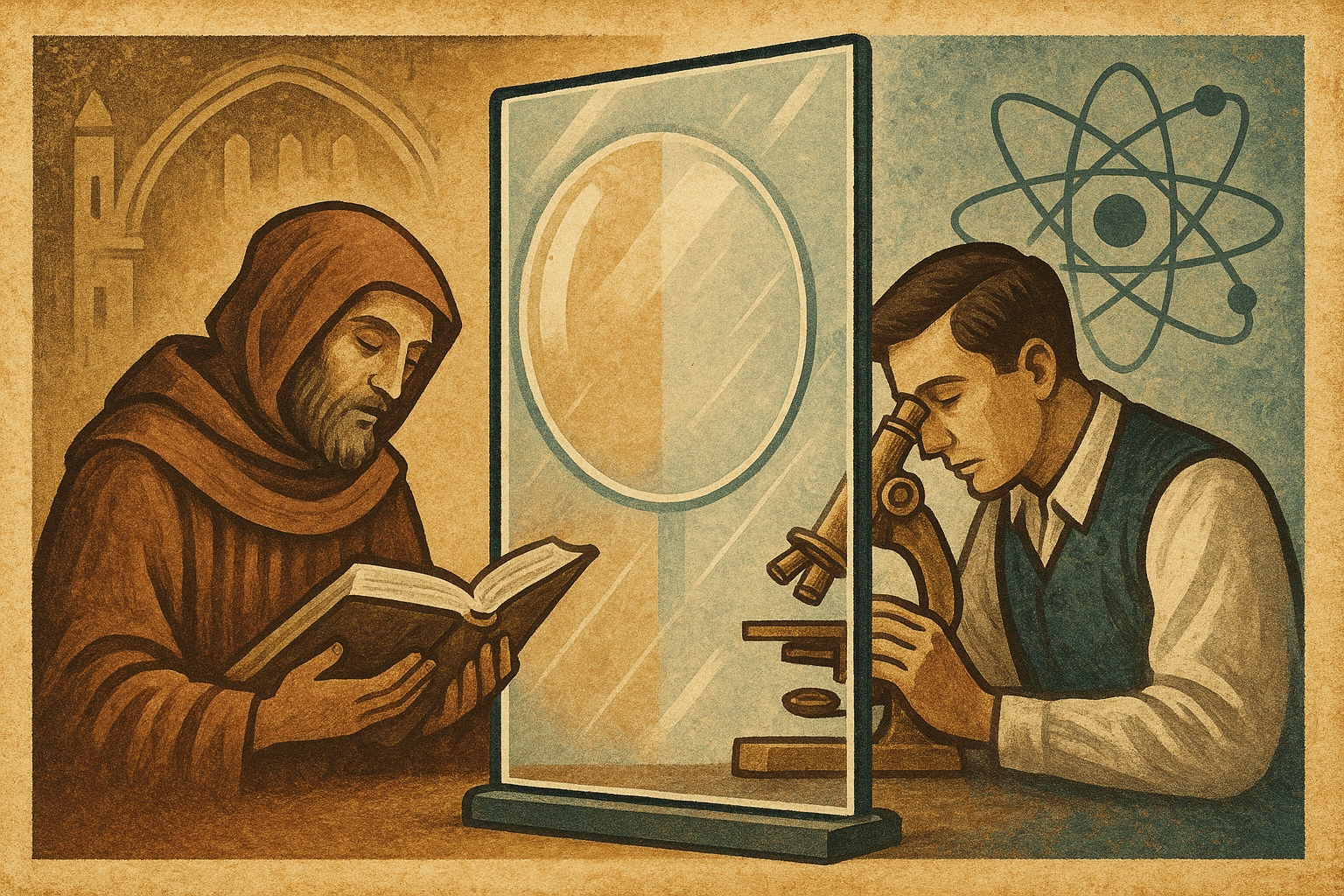

One of the first and most profound impacts of clear glass was the invention of eyeglasses. Before the 14th century, a natural and unavoidable part of aging was presbyopia, the farsightedness that makes reading and close-up work difficult for people over 40. For the average farmer, this was an inconvenience. But for a scholar, a scribe, a lawyer, an accountant, or a skilled artisan like a jeweler or weaver, it was a career-ending catastrophe.

Imagine a world where society’s most experienced and knowledgeable members were forced into retirement just as they reached the peak of their wisdom. An entire generation of expertise was lost every few decades. The first spectacles, consisting of two convex lenses held in a frame, changed everything. Suddenly, a 50-year-old scholar could continue his research, a 60-year-old tailor could still thread a needle, and an aging merchant could pore over his ledgers. This simple invention, made possible by Venetian cristallo, effectively doubled the productive lifespan of the intellectual and skilled classes. It allowed for the accumulation and transfer of knowledge on an unprecedented scale, fueling the very humanism and scholarship that defined the Renaissance.

Revealing Invisible Worlds: The Scientific Revolution

The mastery of grinding lenses for eyeglasses laid the groundwork for an even greater leap. If a simple lens could bring a blurry page into focus, what could more complex arrangements of lenses reveal?

The Infinitesimally Small

In the 17th century, a Dutch draper named Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, using his expertise in examining threads with magnifying glasses, began grinding his own powerful, single-lens microscopes. When he turned them on a drop of pond water, he was stunned. He saw a world teeming with what he called “animalcules”—tiny creatures “swimming” and “tumbling” about. For the first time, humanity witnessed the existence of microorganisms. This discovery shattered the ancient theory of spontaneous generation and laid the foundation for microbiology and germ theory, revolutionizing medicine and our understanding of life itself.

The Infinitely Large

At the same time, others were pointing their lenses in the opposite direction. While not its inventor, Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei dramatically improved the telescope in 1609 and was the first to systematically use it to study the heavens. What he saw dismantled a two-thousand-year-old worldview.

He discovered that Jupiter had its own moons, proving not everything orbited the Earth. He observed the phases of Venus, demonstrating that it orbited the Sun. He saw that the Moon was not a perfect celestial sphere but was covered in mountains and craters. Through two pieces of shaped glass, Galileo provided undeniable evidence for the Copernican heliocentric model. Glass didn’t just let us see farther; it fundamentally changed our place in the universe, demoting Earth from the center of creation to just one planet among many.

Letting the Light In: The Architectural Revolution

Beyond lenses, the ability to produce large, flat panes of clear glass transformed the very spaces where we live and work. Medieval buildings were notoriously dark and gloomy. Openings in the walls were small to conserve heat and were often covered with wooden shutters, oiled paper, or thin sheets of animal horn—materials that let in only a sliver of murky light.

The wider availability of window glass changed architecture from the inside out. For the first time, interiors could be flooded with natural light without exposing inhabitants to the elements. This had massive implications:

- Health and Productivity: Well-lit spaces were healthier, reducing dampness and disease. People could work indoors for longer hours, and tasks requiring fine detail were no longer limited to the brightest daylight hours near an open door.

- Psychological Well-being: The barrier between inside and outside became transparent, creating a visual connection to the natural world that profoundly impacts human comfort and psychology.

- Aesthetic Transformation: Architects were no longer constrained by the need for solid, impenetrable walls. The ability to incorporate large windows, as spectacularly showcased in the Palace of Versailles’ Hall of Mirrors or later in the gargantuan Crystal Palace in London, allowed for buildings that were lighter, more elegant, and expressed a new sense of openness and command over the environment.

From the scholar’s desk to the astronomer’s observatory and the walls of our homes, transparent glass has been a silent and transformative partner in human progress. It is the invisible technology that brought the world, both microscopic and cosmic, into focus. It gave us more time to learn, new worlds to discover, and brighter spaces to live in. The next time you look through a window, remember that you aren’t just looking at the view—you’re looking through one of the most powerful and world-changing inventions in human history.