The Birth of Coinage: From Lumps to Lions

Our story begins around 650 BCE in the Kingdom of Lydia, in what is now modern-day Turkey. Before this, commerce relied on barter or the tedious process of weighing out chunks of precious metal for every transaction. The Lydians had a brilliant idea: why not pre-weigh the metal and stamp it with a mark of authority to guarantee its value?

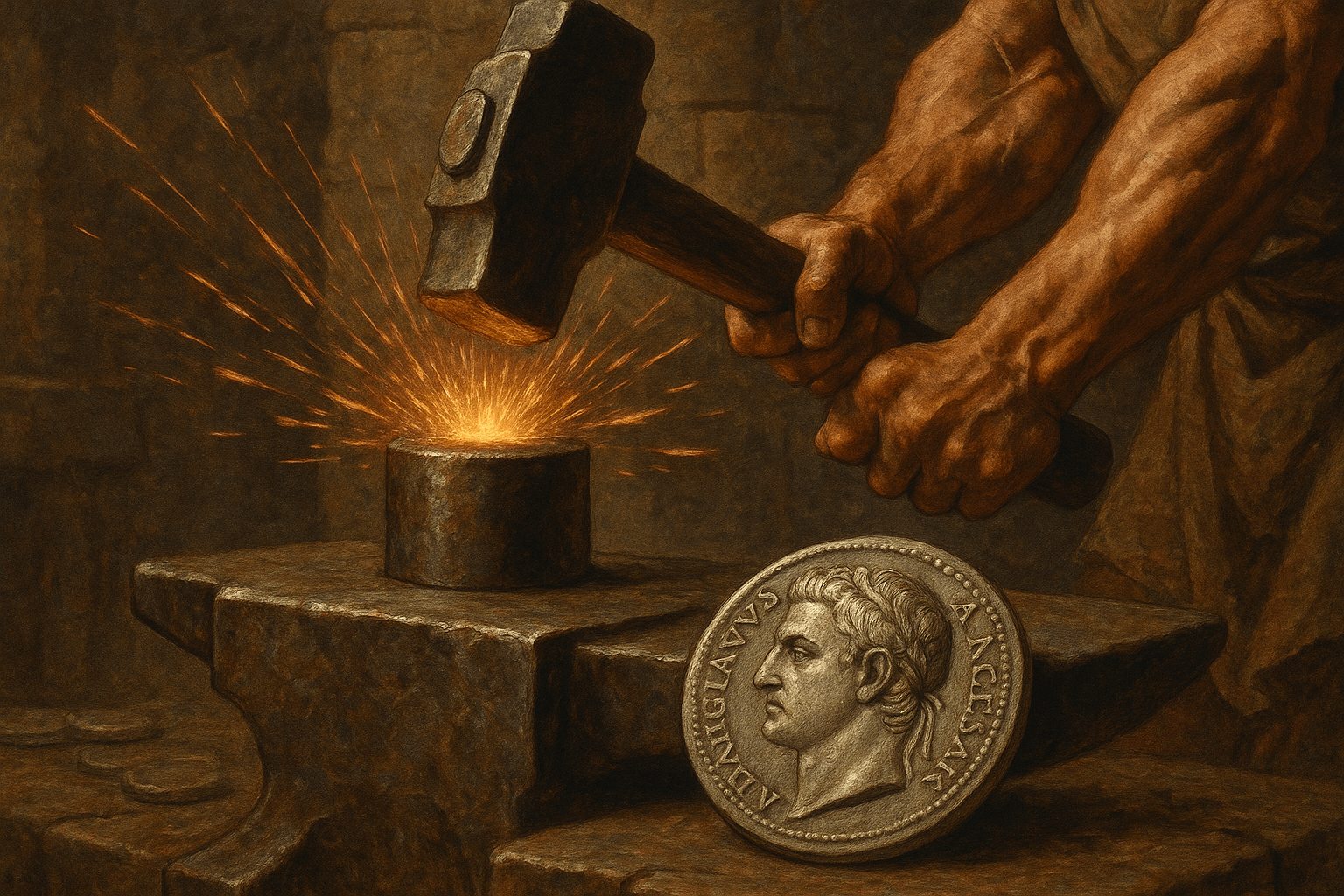

The first coins were made from electrum, a naturally occurring alloy of gold and silver that was plentiful in the rivers of Lydia. The process was rudimentary. A lump of electrum, weighed to a specific standard, was placed on a hard surface that had a design carved into it—this was the anvil die, or obverse die. Then, a simple punch was placed on top of the metal, and a worker would strike it with a heavy hammer. The result was a coin with a sophisticated design on one side (often a roaring lion, the symbol of the Lydian kings) and a crude punch mark on the other. Coinage was born.

Preparing the Metal: The Flan

Before a coin could be struck, the metal had to be prepared. First, the mint had to acquire the raw gold, silver, or bronze. These metals were then refined and, in many cases, intentionally alloyed to achieve a specific standard of purity and durability. For example, Roman silver denarii were initially very pure but were progressively debased over the centuries with copper, a fact that tells its own story of economic hardship.

Once the metal was ready, it was formed into coin blanks, known as flans. There were two primary methods for creating flans:

- Casting: Molten metal was poured into open-faced molds, often shaped like a tray of round depressions. Sometimes, the molds were connected by channels, creating a chain of blanks that looked like a string of beads. Once cooled, these were broken apart, and their edges were roughly smoothed.

- Cutting: Another method involved casting a long metal bar and then cutting off individual slices of the correct weight, much like slicing a loaf of bread.

Regardless of the method, each flan had to be brought to the correct weight. This was a crucial step for ensuring the currency’s integrity. Officials known as moneyers would oversee this process, with individual flans being filed down or adjusted to meet the state-mandated standard. Of course, this was an imperfect, manual process, which is why the weight of ancient coins from the same issue can vary slightly.

The Heart of the Mint: Carving the Dies

The true artistry of ancient coinage lies in the dies. These were the master stamps used to impress the design onto the metal. Typically made of hardened bronze or later, iron, a set of dies consisted of two parts:

- The anvil (obverse) die was the lower die, often set into a large anvil for stability. It usually bore the more important design: the head of a patron deity for a Greek city-state (like Athena on Athenian coins) or the portrait of the emperor in Rome.

- The punch (reverse) die was the upper die, a handheld punch that was struck by the hammer. Because it bore the full, direct force of the hammer blow, this die wore out much more quickly than the anvil die.

The artisans who carved these dies, known as celators, were masters of their craft. Working on a tiny scale, they meticulously engraved intricate designs in negative relief—a task requiring immense skill and precision. The evolution of their art is stunning. Early Greek coins feature stiff, archaic symbolism. By the Classical and Hellenistic periods, these gave way to breathtakingly realistic and beautiful depictions of gods and heroes. In Rome, the die-engravers perfected the art of portraiture, capturing not just the likeness of an emperor but often a sense of their character or political message.

The Moment of Creation: Striking the Coin

With the flans prepared and the dies carved, it was time to strike. The mint was a noisy, hot, and physically demanding workshop. The process was a study in coordinated force.

A mint worker, the “striker”, would take a flan—often heated in a furnace to make it softer and more receptive to the design—and place it with tongs onto the anvil die. Another worker would position the punch die squarely on top of the flan. Then, with a single, powerful swing, a heavy hammer was brought down on the end of the punch die. Clang!

In that instant, the immense force of the blow drove the soft, hot metal into every tiny crevice of both dies. The blank flan was instantly transformed into a coin, bearing the images of the state. This handmade process is responsible for many of the “imperfections” that make ancient coins so fascinating to collectors:

- Off-center strikes: If the flan or the punch die was not perfectly centered, the design would run off the edge of the coin.

- Die cracks: After thousands of strikes, the dies would begin to fatigue and crack. These cracks would appear as raised lines on the coins.

- Ghosting: A faint impression of the design from one side could sometimes appear on the other, a result of metal flowing unevenly during the strike.

Propaganda, Power, and Quality Control

A coin’s design was never just decorative; it was a state-issued message broadcast to the world. In the Greek world, a coin was a city’s calling card. The famous Athenian “Owls” declared the city’s devotion to the goddess Athena and its status as a commercial powerhouse.

For the Romans, coins were the most effective propaganda tool in the empire. Without 24-hour news, the emperor’s portrait on a denarius was how most citizens would ever “see” their ruler. Coins announced military victories (with imagery of captives or trophies), celebrated the completion of new buildings like the Colosseum, and reinforced concepts like peace (Pax) or divine approval (Providentia Deorum). Each coin was a tiny billboard for imperial power and policy.

Quality control focused primarily on weight and metallic purity. Moneyers were responsible for ensuring coins met the standard. However, counterfeiting was rampant. Plated forgeries, known as fourrées, consisted of a base metal core (like copper or bronze) wrapped in a thin layer of silver or gold. To check for this, merchants would often punch a “test cut” into a suspicious coin to reveal the metal underneath, which is why many surviving ancient coins bear these deep gashes.

The next time you gaze upon an ancient Greek tetradrachm or a Roman sestertius, look beyond the image. See the hand of the die-engraver, hear the clang of the hammer, and feel the heat of the forge. You are holding a product of incredible artistry and raw power—a small metal disc that built cities, paid armies, and carried the faces of gods and emperors into history.