Picture a world without cities, without writing, without the wheel. A time 12,000 years in the past, when humanity was comprised of small, nomadic bands of hunter-gatherers. According to the story we’ve always told ourselves, monumental architecture, complex religion, and large-scale social organization were still millennia away, awaiting the spark of the Agricultural Revolution. But nestled in the rolling hills of modern-day Southeastern Turkey, a discovery has shattered that narrative. It’s called Göbekli Tepe, and it’s not just a ruin; it’s a revolution in our understanding of the past.

A Hill with a Bellyful of Secrets

For decades, the hill known locally as Göbekli Tepe (Turkish for “Potbelly Hill”) was just another feature of the landscape. A single mulberry tree at its peak was considered sacred by locals, but the hill itself was thought to be little more than a medieval Byzantine cemetery. Faint traces of an ancient site were noted by archaeologists in the 1960s, but they were dismissed. It wasn’t until 1994 that German archaeologist Klaus Schmidt, re-examining the site, saw what others had missed. The thousands of flint chippings on the surface weren’t just from tool-making; they were the byproduct of a massive, Stone Age undertaking. And the “gravestones” poking out of the soil were not Byzantine at all; they were the tops of enormous, masterfully carved pillars.

What Schmidt’s subsequent excavations revealed was breathtaking. Layer by layer, he and his team uncovered a series of massive, circular enclosures. The oldest of these carbon-date to an astonishing 9,600 BCE. To put that in perspective, this is approximately 6,000 years before Stonehenge and 7,000 years before the Great Pyramid of Giza. These structures were built by people who, as far as all evidence suggests, had not yet domesticated animals, farmed crops, or even made pottery.

The Architecture of a Prehistoric Cathedral

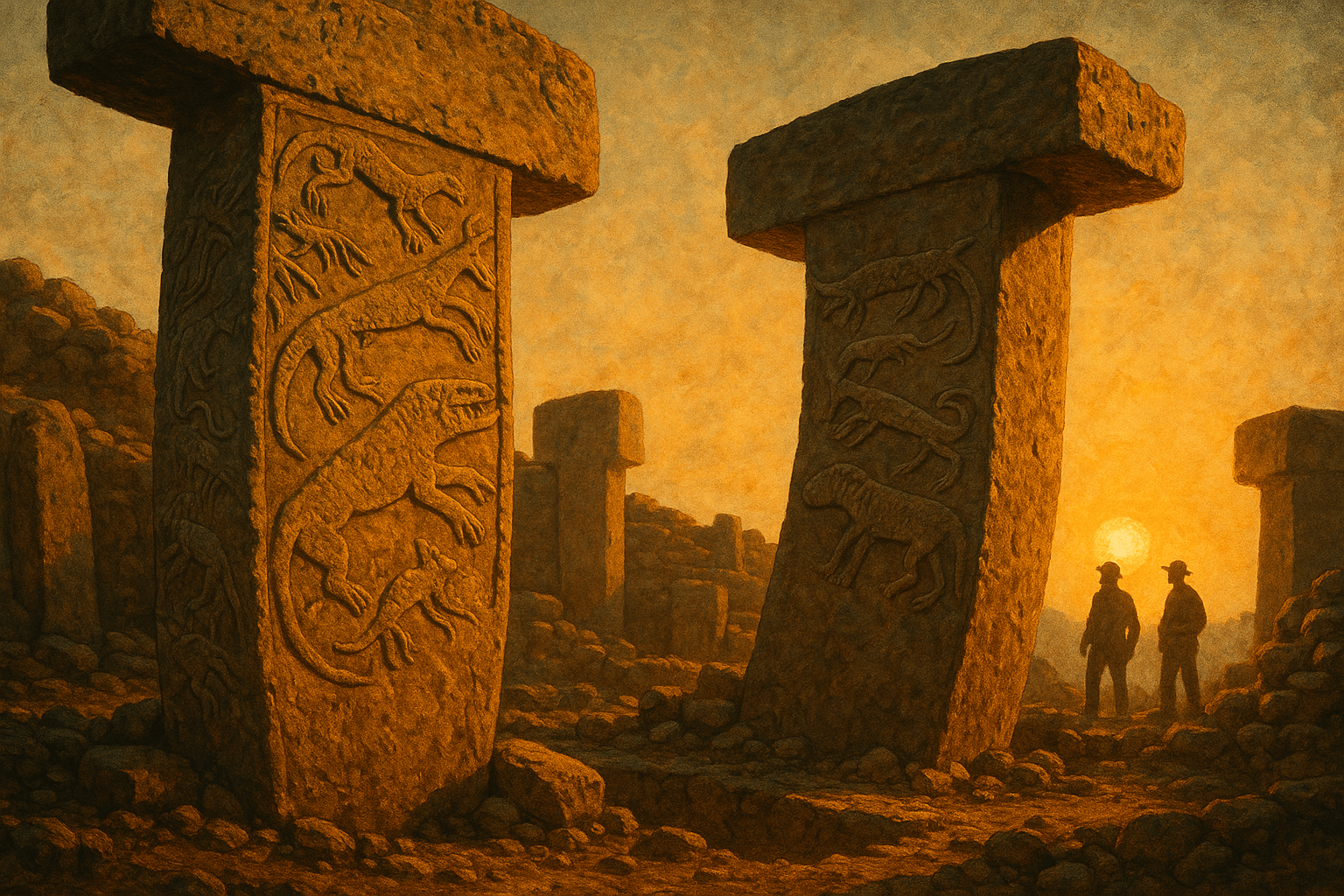

The heart of Göbekli Tepe lies in its monumental T-shaped limestone pillars. Arranged in circles, these monoliths stand up to 18 feet tall and weigh as much as 20 tons. In the center of each enclosure, two even larger pillars stand parallel to each other, forming a focal point. What is truly remarkable is not just their size, but their sophistication.

These are not crude blocks of stone. The pillars are adorned with intricate, high-relief carvings of a Stone Age menagerie:

- Snakes wriggle across the stone surfaces.

- Fearsome boars and powerful bulls appear ready to charge.

- Foxes, gazelles, scorpions, and vultures all feature prominently.

Crucially, these are all wild animals. There are no depictions of sheep, goats, or wheat—the staples of the later agricultural world. The pillars themselves are now widely interpreted as stylized human figures. Carvings of arms, hands, and loincloths can be seen on their sides, suggesting they represent powerful, perhaps divine, beings or revered ancestors, gathered in a circle as if in assembly.

The logistical challenge of constructing Göbekli Tepe is staggering. The builders had to quarry these multi-ton blocks from a nearby limestone plateau, transport them hundreds of meters, and erect them with precision—all without the aid of metal tools, wheels, or beasts of burden. This feat required a level of social organization, planning, and a shared purpose previously thought impossible for hunter-gatherer societies.

Flipping the Neolithic Revolution on Its Head

For over a century, the accepted model of human progress was simple and linear: first came agriculture. The resulting food surplus allowed people to abandon their nomadic lives and form permanent settlements. This stability, in turn, gave rise to specialized labor, social hierarchies, and, eventually, complex belief systems that were expressed through grand temples and monuments. This entire process is known as the Neolithic Revolution.

Göbekli Tepe turns this entire model upside down. The evidence is clear: the builders of this massive ceremonial center were hunter-gatherers. Analysis of animal bones found at the site shows they were hunting wild game, and botanical evidence points to the gathering of wild grasses, like the ancestors of einkorn wheat which still grows wild in the region.

This has led to a radical new theory. What if the desire for organized religion came first? What if the immense effort of building and maintaining a communal ritual site like Göbekli Tepe was the very thing that drove humanity towards civilization? As Klaus Schmidt famously put it, “First came the temple, then the city.” The need to feed the hundreds of workers required for the construction may have pushed local groups to experiment with cultivating wild grains and managing animal herds, kickstarting the process of domestication and leading to the first agricultural settlements.

A Glimpse into the Mind of Our Ancestors

While the site’s function is debated, it was clearly not a place of residence. There are no signs of domestic life—no hearths for cooking, no houses, no everyday garbage pits. This was a place set apart, a sacred destination. It was, in all likelihood, the world’s first temple.

The carvings offer a tantalizing, if cryptic, window into the beliefs of these ancient people. The prevalence of dangerous animals might symbolize a mastery over a hostile natural world or a reverence for its powerful spirits. One of the most intriguing motifs is the vulture. On several pillars, vultures are depicted alongside headless human figures. This has led some scholars to suggest the site was used for funerary rituals, perhaps a form of “sky burial” where the deceased were excarnated—stripped of their flesh by birds—before burial. This theory is supported by the discovery of fragmented human bones, including skulls with deliberate cut marks, within the fill used to bury the enclosures.

The Deliberate Burial

Perhaps one of Göbekli Tepe’s greatest mysteries is its end. Around 8,000 BCE, after more than 1,500 years of use, the site was deliberately and painstakingly buried. The magnificent enclosures were filled with tons of debris, including stone rubble, flint tools, and animal bones. This was no act of destruction; it was a careful, intentional entombment.

Why would its creators inter their own masterpiece? Perhaps the religion it served had changed. Perhaps the rise of agriculture and village life made the old hunter-gatherer rituals obsolete. Whatever the reason, this act of burial is precisely what preserved Göbekli Tepe in a pristine state for 10,000 years, waiting for us to find it.

Today, only about 5% of this vast complex has been excavated. Geophysical surveys show that at least 15 more circular enclosures and over 200 more pillars lie waiting beneath the “potbelly hill.” Göbekli Tepe has already rewritten the first chapter of human civilization. The secrets it has yet to reveal may change the story all over again.