The Fabric of the Ancien Régime: Extravagance and Disconnect

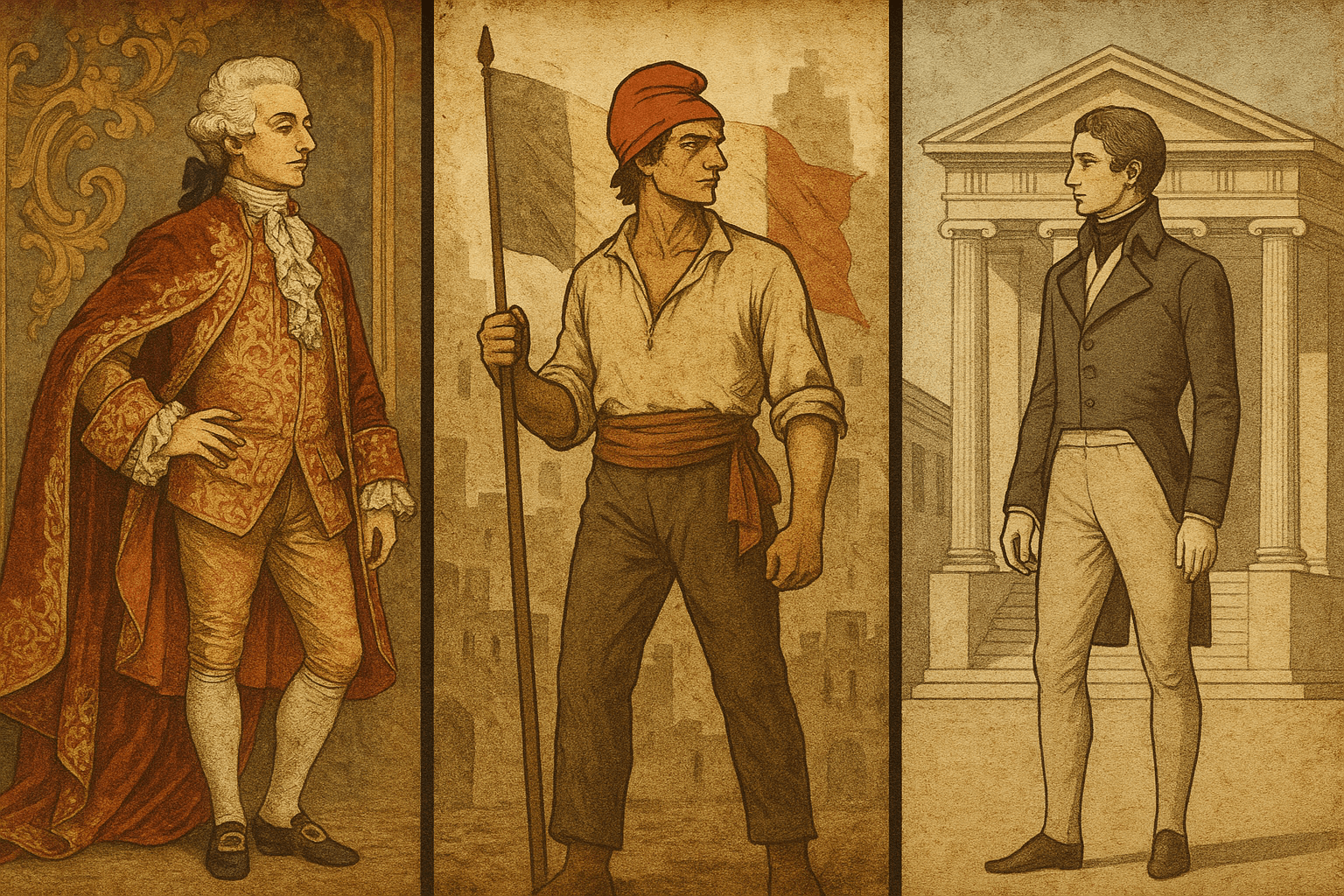

Before the Revolution, French fashion, particularly that of the court at Versailles, was a spectacle of unparalleled luxury. This was the era of the Ancien Régime, a world defined by hereditary privilege and absolute monarchy. The clothing of the aristocracy was designed to communicate one thing above all: immense wealth and a life of complete leisure.

Men of the nobility sported powdered wigs, silk coats embroidered with gold thread, and the all-important culottes—tight, knee-length breeches worn with silk stockings. For women, the look was even more dramatic. Towering, powdered hairstyles called poufs, often decorated with feathers, ribbons, and even model ships, rose a foot or more above the head. Gowns were constructed with wide panniers (hoops) that extended the hips to absurd widths, requiring wearers to turn sideways to pass through doors. The fabrics were priceless silks, satins, and brocades, all crafted by armies of artisans.

This opulent uniform, personified by Queen Marie Antoinette, was more than just impractical; it was a constant, visual reminder of the chasm between the elite and the masses. While the common people starved, the aristocracy flaunted a lifestyle so extravagant it seemed to exist on a different planet. This fashion was a symbol of their perceived frivolity and their profound disconnect from the suffering of the nation. It was clothing that said, “We do not work, we do not struggle, and we are not like you.” It was a look that would ultimately help fuel the fires of revolution.

Dressing for the Revolution: The Sans-Culottes

As revolutionary fervor swept through Paris, a new political figure emerged from the working-class neighborhoods: the sans-culotte. The name itself was a direct fashion statement, meaning “without knee-breeches.” It was a deliberate rejection of the aristocratic culottes and everything they represented.

Instead of silk breeches, the male revolutionary wore pantalons—long, loose-fitting trousers. This was the practical garment of the laborer, the sailor, and the artisan. It symbolized work, utility, and solidarity with the common man. The rest of their “uniform” was equally emblematic:

- The carmagnole: A short, simple woolen jacket, far removed from the embroidered coats of the nobility.

- The sabots: Wooden clogs, the footwear of the poor.

- A simple shirt, open at the neck, defying the frilly cravats of the upper classes.

The sans-culottes’ attire was a uniform of political identity. It was proudly plain, aggressively simple, and unmistakably proletarian. To dress as a sans-culotte was to declare oneself a patriot, a true son of the Revolution, and an enemy of privilege. This clothing celebrated the very labor and poverty that the aristocracy had long scorned.

Symbols of Liberty: The Cockade and the Cap

Beyond the basic garments, two accessories became essential, non-negotiable symbols of revolutionary allegiance. You wore them to prove your loyalty; to be seen without them was to invite accusations of being a traitor or a royalist sympathizer.

The first was the tricolor cockade. Days after the storming of the Bastille in July 1789, a circular rosette of red, white, and blue ribbon appeared. The blue and red were the traditional colors of Paris, while the white was the color of the Bourbon monarchy. The rosette initially symbolized the reconciliation of the king and the people of Paris. However, as the Revolution radicalized, it became purely a symbol of the new French nation. Laws were passed making it mandatory for all citizens to wear the cockade. It was a small, simple object, but its political weight was immense. It was the passport of the patriot.

The second, and even more potent, symbol was the Phrygian cap, or bonnet rouge (“red cap”). This soft, conical cap with the top pulled forward had its roots in antiquity. It resembled the pileus, a cap given to freed slaves in ancient Rome to signify their liberty. For the French revolutionaries, the symbolism was perfect. They saw themselves as casting off the chains of feudal and monarchical “slavery.” The bonnet rouge became the ultimate emblem of freedom and republicanism, famously worn by the sans-culottes and immortalized atop the head of Marianne, the female personification of the French Republic.

The Political Runway: From Terror to Neoclassicism

Fashion continued to evolve throughout the Revolution’s different phases. During the height of the radical Jacobin power and the Reign of Terror (1793-1794), austerity was the rule. Displays of wealth were not only frowned upon but lethally dangerous. A simple, sober style inspired by the sans-culottes was the safest choice.

After the fall of Robespierre and the end of the Terror, a wave of social and stylistic rebellion broke out. The “gilded youth”, known as the Incroyables (“Unbelievables”) and their female counterparts, the Merveilleuses (“Marvelous Women”), rejected the forced austerity of the previous years. They adopted bizarre and exaggerated styles: men wore ridiculously large collars, tight jackets, and shaggy hair, while women donned revealing, semi-transparent dresses inspired by ancient Greece. These high-waisted, un-corseted gowns, known as robe à la grecque, were a statement of liberation from the physical and social constraints of the Ancien Régime. This so-called Neoclassical style also aligned with the Republic’s ideological fascination with the democratic ideals of ancient Greece and Rome.

A Revolution in Silhouette

The French Revolution did more than just overthrow a monarchy; it ripped apart the very fabric of society, and that transformation was visible on the bodies of its citizens. Clothing became a conscious political choice, an immediate signal of one’s place in a new and uncertain world. The powdered wig and silk breeches of the aristocrat gave way to the trousers and red cap of the revolutionary, which in turn were replaced by the “liberated” silhouettes of the new republic.

The revolutionary battlefield was fought not only with guillotines and cannons but also with needles and thread. It serves as a powerful reminder that throughout history, what we wear is never just fashion—it is a reflection of our beliefs, our aspirations, and the societies we wish to create.