While medieval Europe’s approach to medicine was often a mixture of superstition, prayer, and rudimentary herbalism, the Islamic world was experiencing a golden age of science and public welfare. At the heart of this were the Bimaristans—a Persian word meaning “house of the sick”—which were far more than just places to die. They were revolutionary centers of healing, research, and compassion, built on principles that feel remarkably modern.

From Humble Beginnings to Grand Institutions

The concept of institutional healthcare has early roots in Islamic tradition. The first known mobile dispensary was established under the guidance of the Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) himself to treat wounded soldiers on the battlefield. However, the first true, stationary hospital was founded in Damascus around 707 CE by the Umayyad Caliph Al-Walid ibn Abd al-Malik. It was established primarily to care for those with chronic illnesses like leprosy and blindness, providing them with stipends and preventing them from having to beg.

But it was under the Abbasid Caliphate, particularly during the reign of Harun al-Rashid in the late 8th century, that the Bimaristan truly flourished. Inspired by the Persian academy of Gondishapur, al-Rashid established the first great Bimaristan in Baghdad. This set a precedent, and soon, magnificent hospitals began to sprout up across the Islamic world, from Cordoba in Spain to Cairo in Egypt and Rayy in Persia.

More Than Just a Hospital: Design and Function

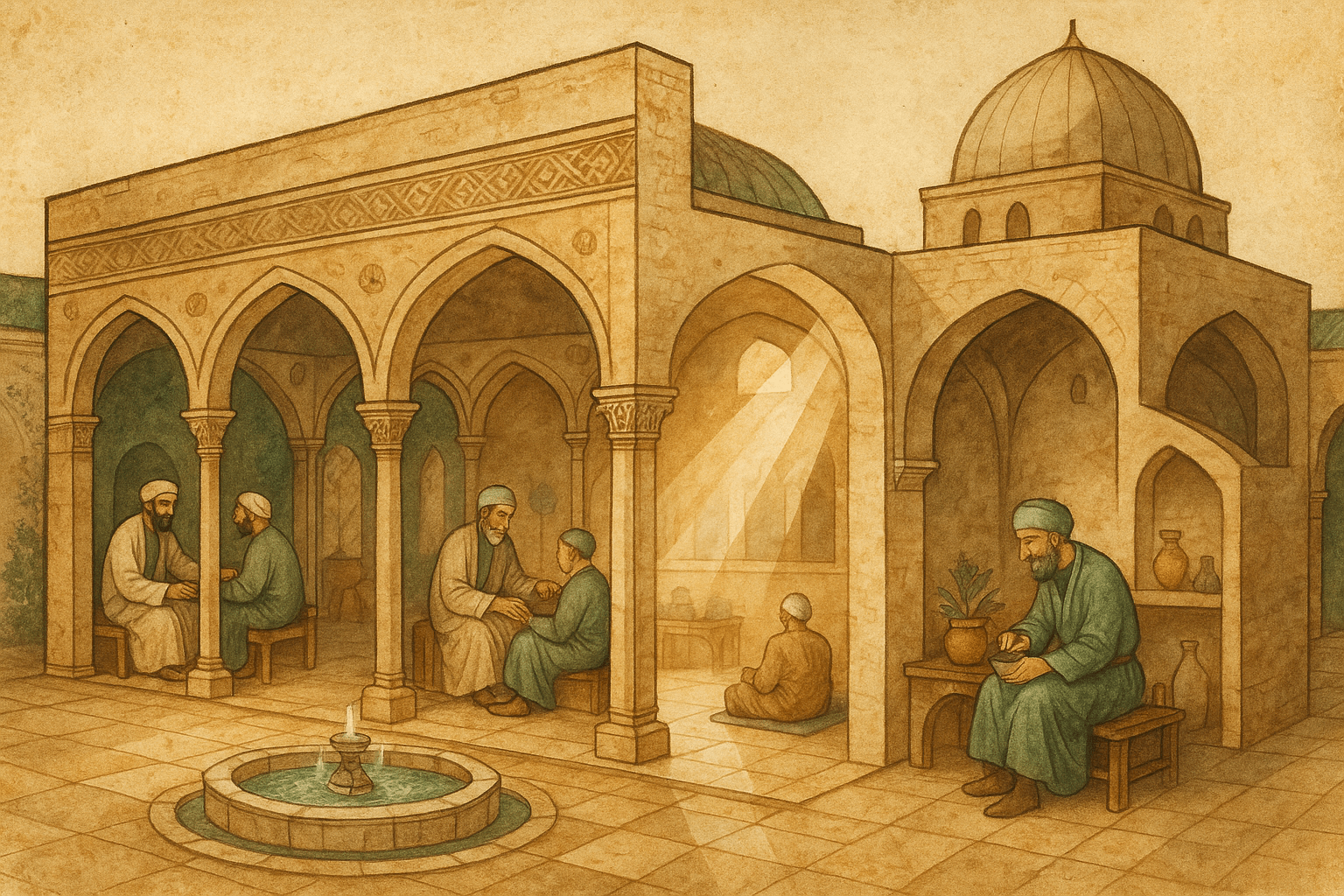

A Bimaristan was not a grim, foreboding place. Architects designed them to be environments conducive to healing. They were often built around a central courtyard with fountains and gardens. The flowing water was not just for aesthetics; it helped cool the

air, provided a source of clean water, and its gentle burbling was thought to soothe the minds of the patients.

The most striking feature was their organization. Patients were separated into different wards based on their ailment, a practice that wouldn’t become common in Europe until much later. A typical large Bimaristan would have dedicated sections for:

- Internal Medicine: For fevers, digestive issues, and other systemic diseases.

- Surgery: For procedures and the setting of fractures.

- Ophthalmology: For eye diseases, a common affliction in the sunny, dusty climate.

- Orthopedics: For bone and joint injuries.

- Mental Illness: Perhaps the most revolutionary of all, these hospitals had dedicated wards for the mentally ill, where they were treated with compassion, music therapy, and restorative care, rather than being chained in dungeons.

Each hospital also had an integrated pharmacy, or saydalana, where licensed pharmacists compounded drugs, syrups, and ointments from a vast repository of materials sourced from across the known world.

A Beacon of Secular Care and Ethical Practice

One of the most profound principles of the Bimaristan was its unwavering commitment to universal care. These were secular institutions, often funded by charitable endowments known as waqf. Their doors were open to everyone, regardless of religion, ethnicity, gender, or social status. A Christian merchant, a Jewish scholar, a Muslim farmer, and a visiting traveler could all receive the same high standard of care, free of charge.

This was underpinned by a strong ethical code. Physicians, like the famed Al-Razi (Rhazes), wrote extensively on medical ethics, emphasizing the duty of the doctor to treat the patient to the best of their ability, without judgment. Upon being admitted, a patient’s clothes and valuables were stored for safekeeping. They were given clean hospital attire and a bed in the appropriate ward. The care was so holistic that upon discharge, recovered patients who had lost their income during their illness were often given a small sum of money to help them get back on their feet.

Centers of Medical Education and Research

Bimaristans were the world’s first true teaching hospitals. They were intrinsically linked to medical schools and vast libraries. Aspiring doctors didn’t just learn from books; they learned through practice. Senior physicians would conduct rounds, followed by a flock of students, discussing cases and treatments at the patient’s bedside—a method still used today.

These institutions were hubs of innovation. Physicians meticulously documented patient case histories, conducted clinical trials on new drugs, and wrote groundbreaking medical encyclopedias. Al-Razi, who was the chief physician of the Baghdad hospital, wrote Kitab al-Hawi (The Comprehensive Book of Medicine), a monumental text that synthesized Greek, Syrian, Indian, and his own clinical observations. Ibn Sina’s (Avicenna’s) The Canon of Medicine, another product of this environment, became the standard medical textbook in both the Islamic world and Europe for over 600 years.

Famous Bimaristans: Legends of Healing

Several Bimaristans became legendary for their scale and quality of care.

- The Adudi Hospital (Baghdad, 982 CE): Founded by the ruler Adud al-Dawla, this hospital employed over two dozen physicians, including specialists, and served as a major medical university.

- The Al-Nuri Hospital (Damascus, 12th Century): For centuries, this was one of the leading medical centers in the world. It famously treated patients for free for three days and housed an enormous library of medical texts.

- The Mansuri Hospital (Cairo, 1284 CE): Perhaps the most impressive of all. Founded by Sultan Qalawun, this colossal complex was reputed to hold thousands of beds. It had separate wards for every conceivable illness, its own laboratories and kitchens, and even employed musicians to play soothing melodies for patients. Its endowment was so vast that it was intended to run in perpetuity, a testament to the founder’s vision of everlasting public service.

A Legacy of Knowledge and Compassion

The Bimaristan was a marvel of the medieval world—a harmonious blend of science, charity, public policy, and education. Its decline began in the later medieval period due to political instability and the disruption of the endowment system. However, its legacy endured. Through translations in Spain and Italy and interactions during the Crusades, the knowledge cultivated within the Bimaristans flowed into Europe, planting the seeds that would eventually blossom into the Renaissance and the modern hospital system.

Today, as we navigate the complexities of modern healthcare, it’s worth looking back at the Bimaristan. It stands as a powerful historical testament to the idea that compassionate, evidence-based, and universally accessible healthcare is one of the highest expressions of a civilized society.