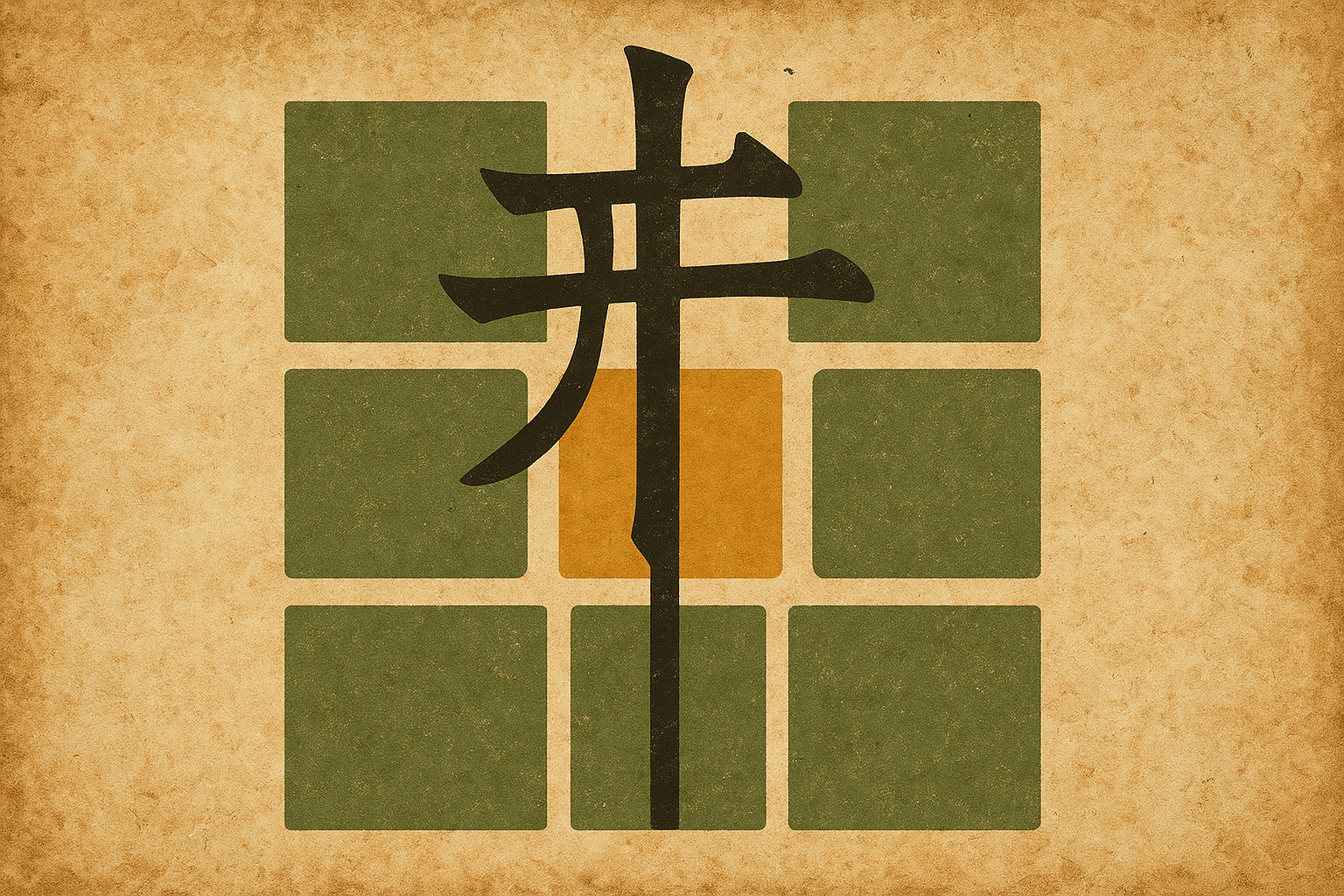

Picture a perfectly ordered landscape in ancient China, more than 3,000 years ago. The land is divided into vast, repeating grids of nine squares, like a massive tic-tac-toe board stretching to the horizon. In each grid, eight families diligently farm their own plots, but before they can tend to their personal crops, they must first work together on the central, ninth square—the public plot, whose harvest belongs to the lord. This is the elegant, egalitarian vision of the “well-field” system, or jǐngtián (井田).

This system, supposedly the bedrock of society during the Western Zhou dynasty (c. 1046–771 BCE), has been held up for millennia as a golden age of social harmony and economic justice. It’s a core concept taught in Chinese history, a symbol of a time before greed and gross inequality. But as with many golden ages, we must ask the critical question: Did it ever really exist on a widespread scale, or is it one of history’s most powerful and enduring political myths?

The Utopian Blueprint

The beauty of the well-field system lies in its simple, symbolic structure. The name itself comes from the Chinese character for “well”, 井 (*jǐng*), which looks exactly like a nine-square grid. The system’s logic was as clear as its geography:

- A large square of land was divided into nine equal plots.

- The eight outer plots were assigned to eight different peasant families as their private land.

- The central plot was the “public field” or “duke’s field.”

- All eight families were required to cultivate the public field collectively before working their own plots. The harvest from this central plot went directly to the local lord or noble as a form of tax and tribute.

In theory, this was a brilliant social contract. The peasants had the security of their own land, giving them a stake in the system and an incentive to be productive. The lord, in turn, received his due without having to manage a complex tax-collection bureaucracy. It embodied the Confucian ideal of a well-ordered society where everyone understood their role and fulfilled their obligations, blending private interest with public duty. It was a vision of stability, self-sufficiency, and communal responsibility. But where did this vision come from?

Whispers in the Texts: The “Evidence”

The primary source for the well-field system is not a dusty government ledger from the Zhou dynasty but the writings of a philosopher who lived hundreds of years later: Mencius (Mengzi, c. 372–289 BCE). Living in the chaotic and bloody Warring States period, Mencius was surrounded by cynical rulers, endless warfare, and crushing poverty. He looked back to the early Zhou dynasty as a lost golden age of benevolent governance.

In his conversations with the kings and princes of his day, Mencius presented the well-field system as a practical blueprint for creating a prosperous and harmonious state. He argued that by providing people with stable livelihoods through this equitable land distribution, a ruler could win their hearts and minds. For Mencius, the well-field system wasn’t just an economic policy; it was a moral imperative. “When the well-fields are not cultivated”, he warned, “the royal coffers are not full.”

The problem is that Mencius was using history as a rhetorical tool. He was a philosopher, not a historian. He was prescribing an ideal to critique his present, not describing a past reality. Later texts, such as the Rites of Zhou, also describe this and other idealized Zhou institutions, but these were compiled long after the fact and are now largely seen by historians as utopian constructions, not accurate administrative records.

The Silence of the Spade: The Archaeological Problem

While the textual tradition is rich with praise for the well-field system, the ground tells a different story. For a system so fundamental and widespread, we would expect to find some trace of it in the archaeological record. Yet, despite decades of extensive archaeology throughout China, the evidence is simply not there.

- No Physical Evidence: Archaeologists have found no remains of ancient field patterns that match the rigid, geometric 井 grid. Land use in ancient China, as elsewhere, appears to have been shaped by practical considerations like terrain, water sources, and soil quality—not by an abstract, symmetrical template. The idea of imposing a perfect grid over diverse landscapes of hills, rivers, and valleys is logistically mind-boggling.

- No Contemporary Records: Even more damning is the silence from the Western Zhou period itself. Our primary contemporary sources from that era are inscriptions on bronze ritual vessels and, to a lesser extent, oracle bones. These inscriptions record royal decrees, land grants, military victories, and legal disputes. Nowhere in these thousands of authentic Zhou texts does the term jǐngtián or a description of its nine-square structure appear. The very people who supposedly lived under this system never wrote about it.

This glaring lack of evidence has led most modern historians to conclude that the well-field system, as described by Mencius, was not a historical reality. It may have existed as a small-scale local practice in some very flat, idealized area, or it may have been an entirely theoretical concept. Either way, it was certainly not the universal system of the Western Zhou.

The Power of a Political Myth

If the well-field system never truly existed, why is it so famous? Because its power was never in its reality, but in its potential as an idea.

Throughout Chinese history, the jǐngtián has served as a powerful symbol for reformers and rebels alike. It became the ultimate utopian ideal for anyone seeking to address the perennial problem of land inequality.

The most dramatic example was Wang Mang, the “usurper” emperor who founded the short-lived Xin dynasty (9–23 CE). A Confucian scholar, Wang Mang took the classics literally. He sought to solve a growing agrarian crisis by nationalizing all land and reinstituting a version of the well-field system. His radical reforms were a catastrophic failure. They were impossible to implement and led to widespread chaos and rebellion, ultimately costing him his throne and his life.

Centuries later, the leaders of the Taiping Rebellion (1850–1864), a massive Christian-inspired peasant uprising, proposed their own radical land reform program. Their “Land System of the Heavenly Dynasty” called for all land to be held in a common treasury and distributed for use based on need, echoing the egalitarian spirit of the ancient well-field myth.

The well-field system, therefore, tells us less about the actual economics of the Zhou dynasty and more about the enduring aspirations of Chinese political thought. It represents a deep-seated belief in the moral responsibility of the state to ensure the people’s welfare and a recurring dream of a society free from the injustices of landlessness and exploitation.

In the end, the well-field system is a historical mirage. It was likely a beautiful idea born of a philosopher’s nostalgia, a vision of order projected onto a distant past to make sense of a chaotic present. While it may not have been real, the myth of the well-field system became a historical force in its own right, inspiring reformers and shaping debates about justice and governance for over two thousand years.