Setting the Stage: The Cost of an Empire

To understand the debates, we must first look back to the long and consequential reign of Emperor Wu of Han (r. 141–87 BCE), also known as the “Martial Emperor.” His name was well-earned. Emperor Wu was an expansionist who pushed China’s borders deep into Central Asia, Vietnam, and the Korean peninsula. His greatest and most expensive endeavor was a decades-long war against the nomadic Xiongnu confederation to the north, a persistent threat to the empire’s stability.

These campaigns, along with massive infrastructure projects like extending the Great Wall, were cripplingly expensive. The traditional land and poll taxes levied on peasants were not nearly enough to fund the emperor’s ambitions. The treasury was on the brink of collapse.

Faced with a fiscal crisis, Emperor Wu and his chief minister, the brilliant but ruthless legalist Sang Hongyang, implemented a radical economic policy. They established state monopolies over the production and sale of two of the era’s most essential commodities: salt and iron.

- Salt: A crucial dietary staple for all, essential for preserving food.

- Iron: The basis of military might (weapons) and agricultural productivity (tools like plowshares and hoes).

By controlling these industries, the government could set prices, eliminate private competition, and direct a massive stream of revenue straight into the state’s coffers. From a purely financial standpoint, it was a stunning success. The monopolies funded the armies that secured the frontiers. But this success came at a steep social cost, sowing the seeds for the great debate to come.

The Two Sides: Modernists vs. Reformists

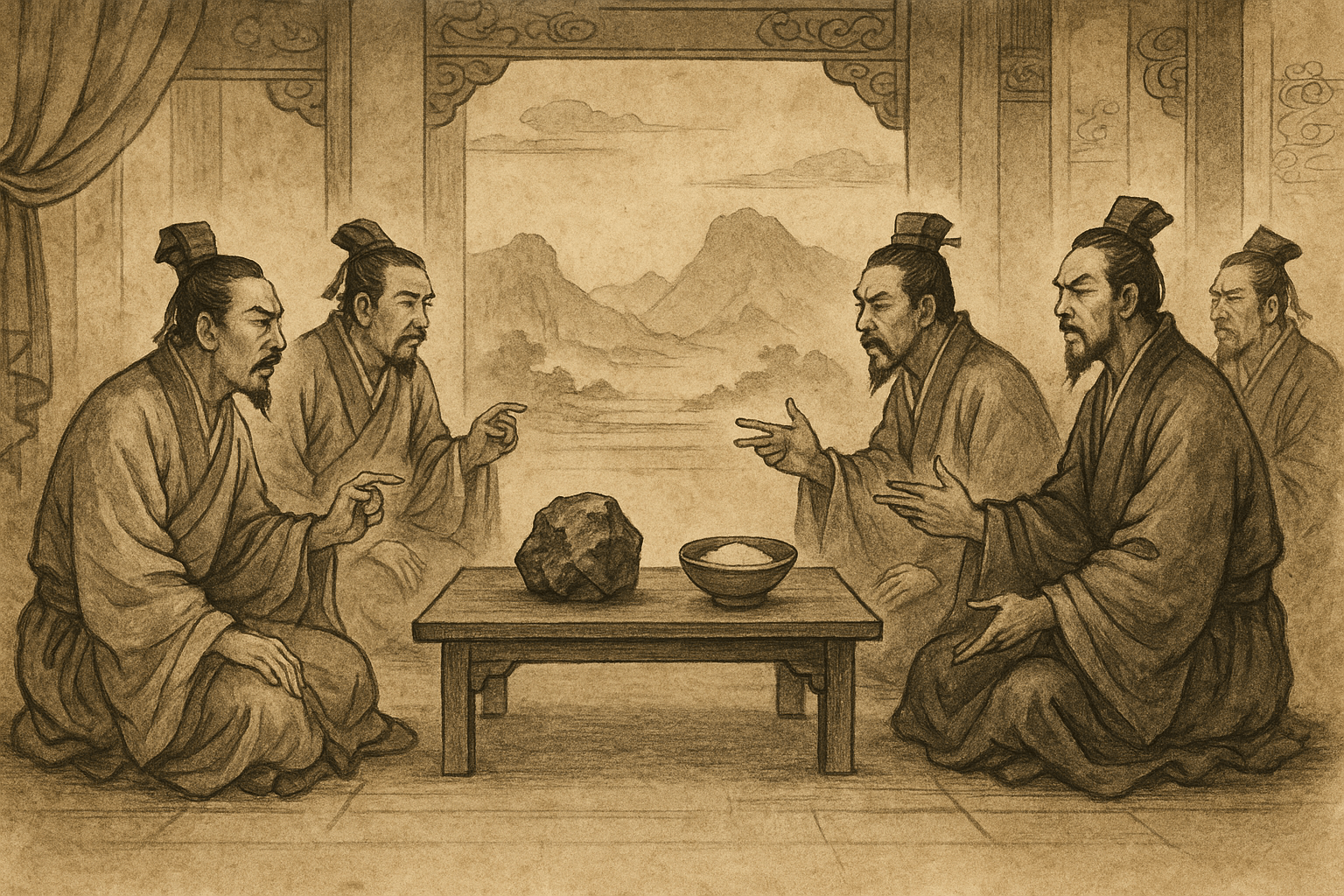

After Emperor Wu’s death, the political climate shifted. The hardships caused by his policies led to widespread discontent. In 81 BCE, the regent Huo Guang, ruling for the young Emperor Zhao, convened a grand council. He summoned scholars and notables from across the empire to voice the concerns of the people directly to the central government, represented by Grand Secretary Sang Hongyang.

Two clear factions emerged from this assembly.

The Modernists (Legalists)

Led by the architect of the monopoly system himself, Sang Hongyang, this group represented the central government’s interests. Their philosophy was pragmatic, state-centric, and rooted in the Legalist tradition, which prioritized order and state power above all else.

Their arguments were compellingly practical:

- National Security: The monopolies were a matter of survival. Without this revenue, the army on the northern frontier could not be supplied. A weak defense would invite Xiongnu raids, leading to far greater suffering than high-priced iron.

- Economic Stability: State control prevented greedy private merchants from hoarding resources, manipulating prices, and accumulating vast fortunes that could challenge state authority. The government, they argued, could ensure a more equitable distribution and stable supply.

- National Unity: A strong, well-funded central government was necessary to hold a vast empire together.

The Reformists (Confucians)

This group was a collection of Confucian scholars who championed the welfare of the common people, particularly the peasantry. Their philosophy was based on morality, tradition, and the teachings of Confucius.

Their arguments were a direct moral and economic critique of the government’s policies:

- Immorality of State Profit: They argued that a virtuous ruler should lead by moral example, not by scrambling for profit (利, lì) like a common merchant. The government’s role was to promote righteousness (義, yì) and care for its people, not compete with them in the marketplace.

- Harm to the People: The state-run foundries, they claimed, produced shoddy, brittle iron tools that were sold at inflated prices. Farmers were forced to work with inferior equipment, leading to lower crop yields and greater hardship. The state’s salt was often impure and expensive.

- Primacy of Agriculture: Following classic Confucian thought, they believed agriculture was the “root” (本, běn) of society, while commerce and crafts were the “branches” (末, mò). The state’s focus on industrial production and trade was seen as a perversion of the natural order, neglecting the well-being of the farmers who were the empire’s foundation.

The Heart of the Argument: A Clash of Worldviews

The Discourses on Salt and Iron, the text that records these debates, reveals a profound clash of worldviews. When the Reformists complained about the poor quality of state-made iron tools, Sang Hongyang essentially retorted that the tools were made for the rugged conditions of the frontier, not the pampered fields of the interior provinces. It was a classic case of two sides talking past each other.

The Reformists declared: “To have the government monopolize salt and iron… is to institutionalize a system that strives for profit with the people. How can this be used to guide them toward propriety and righteousness?”

Sang Hongyang countered: “If we were to abolish the salt and iron monopolies… our frontier financial resources would be insufficient. How would we provide for the soldiers defending our strategic posts?”

The debates were a proxy war for a larger question: What is the fundamental purpose of government? Is it to provide a secure and stable framework for the nation, using whatever means necessary? Or is it to cultivate a moral and prosperous society from the ground up, trusting that virtue will bring its own strength?

The Verdict and its Lasting Legacy

In the immediate aftermath, neither side achieved a total victory. The Modernists largely won the day on a practical level. The state was too dependent on the revenue, and the threat from the Xiongnu was too real. The monopolies on salt and iron, the cornerstones of the system, remained in place for most of the Han Dynasty and were revived by later dynasties in times of fiscal need.

However, the Reformists won the long-term ideological war. Their arguments were meticulously recorded and became a canonical text in Chinese political philosophy. The ideal of a benevolent, non-interventionist government that prioritized agriculture and ruled through moral suasion became the dominant Confucian orthodoxy for the next two millennia.

The Salt and Iron debates of 81 BCE are more than just a historical curiosity. They represent one of the earliest and most sophisticated public discussions on economic policy in human history. The tension between the Modernists and Reformists is a timeless one:

- State-owned enterprise vs. private industry.

- National security priorities vs. domestic welfare.

- Free markets vs. government regulation.

- The role of government as a pragmatic provider or a moral guide.

Fast forward over 2,000 years, and we see these same debates playing out in parliaments and on news channels around the world. Every argument over funding for defense, the regulation of big tech, or the merits of nationalized healthcare contains an echo of the Han Dynasty scholars who fought not with swords, but with powerful ideas about the proper relationship between the state, its people, and its economy.