Imagine a world without paper money. To buy your groceries, you don’t pull out a wallet with crisp bills, but a heavy pouch of metal coins. To make a large purchase—say, a new horse or a plot of land—you’d need a cart, not a purse. This was the reality for most of human history. Yet, over a thousand years ago, in the bustling commercial heart of Song Dynasty China, an invention emerged that would forever change the nature of commerce: paper currency.

This is the story of the jiaozi, the world’s first paper money—a revolutionary concept born of necessity that fueled an economic boom and introduced the world to the modern problem of inflation.

A Pocketful of Problems: The Burden of Coin

The Song Dynasty (960-1279 AD) was a period of incredible economic vitality in China. Cities swelled, trade flourished, and a vibrant merchant class emerged. But this prosperity created a logistical nightmare. The standard currency consisted of copper or iron coins, cast with a square hole in the middle so they could be strung together. For small transactions, this was manageable. For large-scale commerce, it was excruciatingly cumbersome.

The problem was most severe in the remote and prosperous region of Sichuan. Rich in salt, tea, and textiles, Sichuan was a hub of commercial activity. However, it was poor in copper. To preserve its copper supply for other regions, the government mandated that Sichuan use heavy iron coins for all its transactions. The exchange rate was punishing: it could take up to ten iron coins to equal the value of a single copper one.

A single string of 1,000 iron coins could weigh over 25 pounds (about 11 kg). A significant merchant transaction, like buying a bolt of silk, could require a wheelbarrow filled with metal. The sheer weight and volume of the currency were strangling the very commerce it was supposed to facilitate. Merchants were desperate for a better way.

An Ingenious Solution: The First “Jiaozi”

The solution didn’t come from the imperial court, but from the practical ingenuity of the merchants themselves. In Sichuan’s capital city of Chengdu, a group of sixteen wealthy merchants and financiers created a system of private deposit shops known as jiaozi pu.

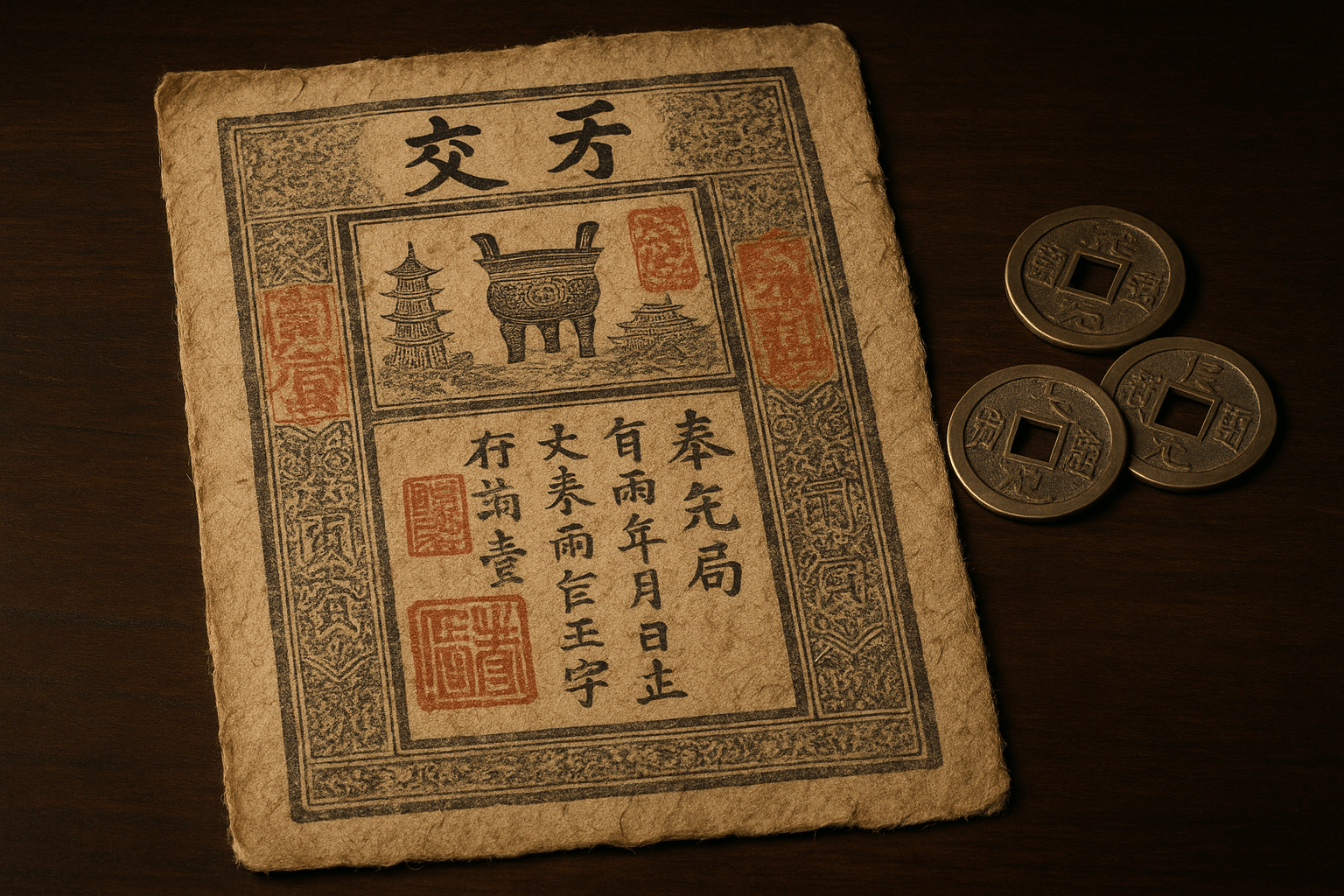

The idea was simple but brilliant. A merchant could deposit his heavy strings of iron coins at one of these trusted shops. In return, he would receive a paper certificate—a “jiaozi”—as a receipt. This certificate was a promissory note, a written promise from the deposit shop to pay the bearer the equivalent amount in coin on demand. Printed on special paper made from mulberry bark, these notes featured intricate designs, secret marks, and the seals of the issuing houses to discourage counterfeiting.

These early jiaozi became a trusted medium of exchange. Instead of hauling carts of iron, merchants could settle a large debt by simply handing over one of these lightweight paper notes. The recipient trusted that they could, at any time, redeem the note for its full value in coin at the shop that issued it. For a small service fee, commerce was suddenly liberated from the tyranny of weight. This system, where paper represents a “promise to pay” in hard currency, was the foundation of representative money.

The State Steps In: The World’s First National Paper Currency

This private system worked well for a few decades, but it was unregulated and vulnerable. Some deposit shops, tempted by greed, issued more notes than they had coins in reserve. Others went out of business, leaving their jiaozi holders with worthless paper. Disputes and fraud began to threaten the stability of the system that everyone had come to rely on.

The Song government, recognizing both the immense potential of paper money and the dangers of an unregulated system, decided to intervene. In 1024 AD, the imperial court made a historic move: it outlawed all private issuance of jiaozi and took over the entire operation. It established a government bureau in Sichuan—the world’s first central bank of sorts—to issue a standardized, state-backed paper currency.

These official jiaozi notes were far more sophisticated. They were printed using multiple colors of ink, stamped with official government seals, and carried warnings that counterfeiters would be beheaded. Each series of notes had a set expiration date, usually two or three years, after which they had to be turned in for new ones. This prevented old, worn-out notes from circulating and gave the government a measure of control. With this act, the Song Dynasty had officially created the world’s first government-issued paper money.

Boom and Bust: Commerce, Warfare, and the Ghost of Inflation

The impact of government-backed jiaozi was immediate and profound. It supercharged the Song economy. Long-distance trade in tea, salt, and silk flourished as B. merchants could now travel light. The government found it an incredibly efficient way to pay its soldiers stationed on the frontiers and to fund massive public works projects.

But this powerful new tool had a dangerous side. The Song Dynasty was under constant military pressure from northern nomadic groups, particularly the Jurchens. Wars were incredibly expensive, and the government soon faced a budget shortfall. The temptation to simply print more money to cover its expenses, without having the metal coins to back it up, proved irresistible.

At first, the government printed cautiously. But as military pressures mounted, the printing presses ran faster and faster. The government issued vast quantities of jiaozi that were not fully backed by its reserves of iron and copper. The inevitable happened: the public lost faith in the paper. A jiaozi note that was once worth 1,000 coins was soon only accepted for a few hundred, then for a handful, and eventually, for almost nothing. Prices for everyday goods skyrocketed as people demanded more and more of the devalued paper for the same products. The Song Dynasty had just given the world its first lesson in state-sponsored hyperinflation.

The Enduring Legacy of “Flying Money”

The jiaozi was eventually discontinued due to its collapse in value, replaced by a new form of paper currency called the huizi. But the principle had been established. Throughout subsequent dynasties like the Yuan, paper money—nicknamed “flying money” for its light weight—remained a feature of the Chinese economy. When the Venetian merchant Marco Polo traveled through Yuan China in the 13th century, he was astonished by the concept of the state creating money from the bark of a tree, an idea completely alien to Europe at the time.

His accounts helped carry the idea westward, though it would take several more centuries for European governments to fully embrace it. The story of the jiaozi is a microcosm of modern monetary policy. It demonstrates the brilliant utility of fiat currency in stimulating an economy, while also serving as a stark warning of the dangers of inflation when governments print money irresponsibly. The challenges the Song officials faced—maintaining public trust, managing the money supply, and balancing the budget—are the very same challenges that confront the world’s central bankers today.

The humble jiaozi note from Sichuan was more than just a piece of paper. It was a pivotal invention that reshaped an empire and laid the monetary foundation for the global economy we know today.